rhyme

What Is Rhyme? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

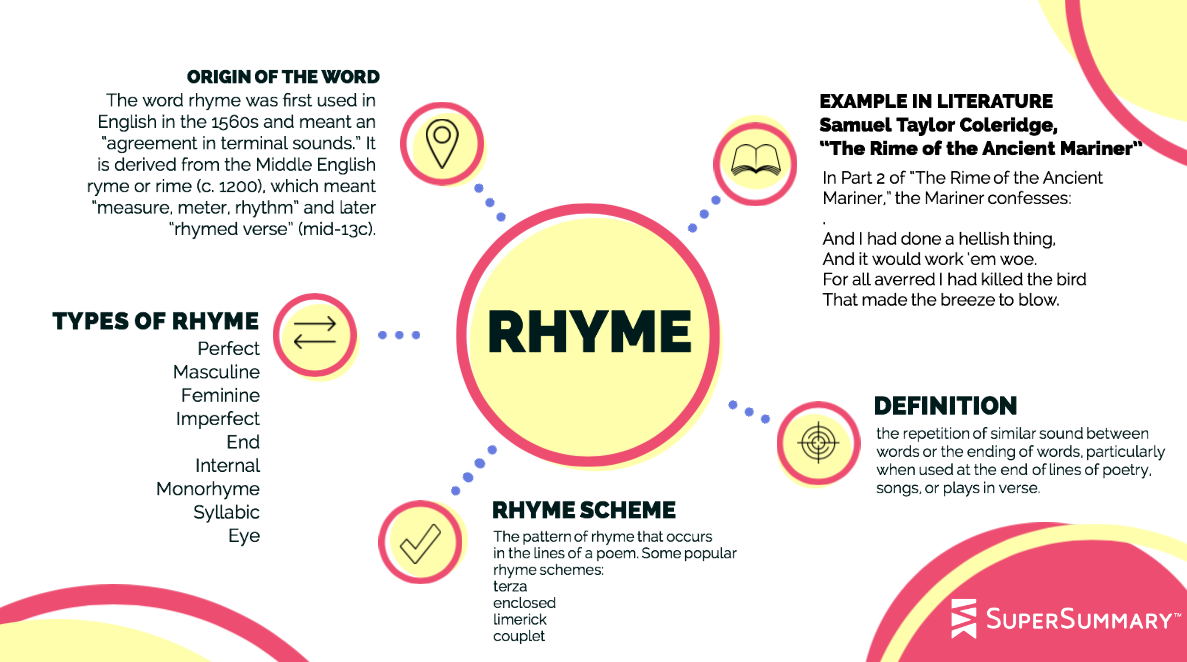

Rhyme Definition

Rhyme (RYEm) is the repetition of a similar sound between words or the ending of words, particularly when used at the end of lines of poetry, songs, or plays in verse.

The word rhyme was first used in English in the 1560s and meant an “agreement in terminal sounds.” It is derived from the Middle English ryme or rime (circa 1200), which meant “measure, meter, rhythm” and later “rhymed verse” (mid-13th century). The Middle English word was derived from the Old French, from the medieval Latin rithmus. Rhyme’s current English spelling was introduced in the early 17th century.

Types of Rhyme

There are many types of rhyme. The following are some of the most common types.

Perfect Rhyme

This type of rhyme occurs when the sound of stressed syllables in two or more words are identical. For example, dog and log are perfect rhymes. Although their initial consonants are different (d and l), the emphasized vowel sound (the short o) and the concluding consonant (g) are an exact match. Perfect rhymes don’t have to be monosyllabic. The first, stressed syllable and the concluding syllable of blunder and thunder share identical sounds, so these words are perfect rhymes. Perfect rhymes are also often called true rhymes, exact rhymes, or full rhymes.

In poetry, perfect rhymes allow writers to precisely follow the conventions of certain poetic forms—for instance, the sonnet or the pantoum. Perfect rhyme also creates anticipation in the reader, who can intuit what words may arrive next, and can serve as a mnemonic device that makes it easier for readers to memorize a text. Perfect rhymes can be classified into subcategories based on the number of syllables included in the rhyme, such as single (masculine) rhymes, double (feminine) rhymes, and dactylic rhymes (where the stress is on the third-from-last, or antepenultimate, syllable).

Masculine Rhyme

This term, which has nothing to do with gender, indicates rhymes that occur only on the stressed final syllables of the rhyming words. An example of masculine rhymes would be John Donne’s poem “Death Be Not Proud”:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those, whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

The word pairs thee and me and so and overthrow are masculine rhymes.

Feminine Rhyme

This most commonly occur when the rhyming words have two syllables, and the second syllable is unstressed. For instance, ocean and motion are feminine rhymes; both words contain a long o sound in the first syllable and an identical-sounding unstressed second syllable. This is also called a double rhyme.

Feminine rhymes can be made using three syllables as well. In this case, both the second and third syllables are unstressed, such as beautiful and dutiful. This can be referred to as triple rhymes.

Imperfect Rhyme

An imperfect rhyme consists of words with similar but not identical sounds. These rhymes can occur when words’ vowel sounds don’t match but the stressed syllables of the ending consonants do. For instance, song and young have similar ending consonants, but their vowel sounds are different. Imperfect rhyme can also occur when the stressed syllable of one word rhymes with the unstressed syllable of another word, such as blaring and wing or uptown and down.

Imperfect rhymes have several other names: slant rhymes, half rhymes, forced rhymes, oblique rhymes, sprung rhymes, off rhymes, lazy rhymes, or near rhymes. They’re a common literary device in poetry as they help poets utilize a wider range of words to keep their poems interesting. It also allows poets to avoid the sing-song effects of perfect rhyme, thus imbuing poems with a more varied and complex texture.

End Rhyme

This type of rhyme is the most commonly used rhyming structure in poetry and songs. End rhymes occur when the last words or syllables in two or more lines rhyme. Poets use end rhyme to create a musical pattern that creates anticipation for readers and helps them memorize the work. End rhymes are also called tail rhymes.

Consider Chelsea Rathburn’s poem “Postpartum: Lullaby,” which ends with:

and still they rock and rock and rock

beside a cold indifferent clock.

These lines contain end rhymes; rock and clock rhyme with each other.

Internal Rhyme

There are multiple ways internal rhymes can appear in a line of poetry. If a word in the middle of the line rhymes with the word at the end of that same line, it is an internal rhyme. This type of rhyme also occurs when a middle word rhymes with a middle word from a separate line of poetry, or when middle and end words in multiple lines rhyme. The repetition of sound that occurs with the use of internal rhyme helps create a powerful hypnotic effect on the reader and enhances the musicality of the work. Internal rhymes are also called middle rhymes.

Edgar Allen Poe utilizes internal rhyme in the poem “Annabel Lee”:

For the moon never beams without giving us dreams.

Monorhyme

This style uses the same end rhyme throughout a poem or within a specific stanza or section. The term is easy to remember as mono means “one.” Monorhymes rarely occur in poems written in English, but they are common in Arabic, Latin, and Welsh verse.

Syllabic Rhyme

When the last syllable of rhyming words doesn’t contain identical stressed vowels but still sounds the same, it’s called a syllabic rhyme. For example, pitter and patter or fiddle and bottle are syllabic rhymes.

Eye Rhyme

Rhyming words that are spelled similarly but pronounced differently are eye rhymes—for example, love and move. This type of rhyme is also called a visual or sight rhyme.

Many older poems, especially those written in Middle English, appear to contain eye rhymes; however, those rhymes were originally perfect rhymes. Modern readers interpret them as eye rhymes because of shifts in pronunciation over the centuries. These are called historic rhymes. For example, consider these lines from Hamlet:

The great man down, you mark his favourite flies;

The poor advanced makes friends of enemies

When Shakespeare originally wrote these lines, the words flies and enemies rhymed. In contemporary pronunciation, the words no longer rhyme, thus making them eye rhymes.

Rhyme and Rhyme Scheme

Rhyme scheme refers to the pattern of rhyme that occurs in the lines of a poem. While most contemporary poems are written in non-rhyming free verse, historically most poems were written according to specific rhyme schemes that corresponded with the poem’s form was written in (for example, Elizabethan or Petrarchan sonnets).

When people discuss rhyme schemes, they use letters of the alphabet to indicate the repeating patterns. For example, if someone were describing a six-line poem that uses an alternating rhyme scheme, they would write it out like this: ABABAB.

Types of Rhyme Scheme

Some popular rhyme schemes include:

- A terza rima is a rhyme scheme that applies to tercets (three-line stanzas). The terza rima is composed with a pattern of end rhymes where a stanza’s second line rhymes with the first and third lines of the following stanza. It looks like this: ABA BCB CDC DED EFE etc.

- An enclosed rhyme uses an ABBA rhyme scheme.

- A limerick is a poem consisting of five lines with the rhyme scheme of AABBA.

- A couplet is a poem made of two-line stanzas that follow a rhyme scheme of AA BB CC and so on. Couplet can also refer to the two-line stanza itself, as the sonnet form contains 12 lines of poetry followed by an ending couplet.

Why Writers Use Rhyme

When used, the repeating sonic patterns of rhyme bring musicality and rhythm to poems, thus differentiating them from prose and free verse. Rhyme adds a lulling, calming effect to poems as it allows readers to anticipate subsequent sonic repetitions and immerse themselves in that pattern. Rhyme is also a useful mnemonic device as the repetition of each similar sound creates a framework for easy memorization.

Rhyme in Children’s Literature

Children’s literature uses rhyme because it is musical and pleasurable. The repetition of identical sounds has a calming effect that can be soporific, helping lull young children to sleep. Using clearly established rhyming patterns in illustrated books can also help with literacy because children can begin to anticipate the next rhymed word.

Nursery rhymes are some of the first pieces of literature children are exposed to, and as the name suggests, they all rhyme; for example: “Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall. Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.” The predictable rhyming patterns of nursery rhymes help children memorize them.

Longer-form children’s literature often uses perfect rhyme, internal rhyme, and end rhyme. For example, in the classic children’s book Goodnight Moon, author Margaret Wise Brown describes the contents of the room: “[…] three little bears sitting on chairs / And two little kittens / And a pair of mittens.” The first line contains an internal rhyme (bears and chairs) and the next two lines contain an end rhyme (kittens and mittens).

Rhyme in Songs

Every genre of music that contains lyrics utilizes rhyme. From pop songs to opera to rap and beyond, lyricists create symmetry and rhythm with rhyme. Musicians make use of the same types of rhyme as poets—such as end rhyme, internal rhyme, perfect rhyme, and imperfect rhyme—as well as a variety of rhyme schemes.

- In Prince’s classic pop song, “Sign O’ The Times,” he sings: “a skinny man died of a big disease with a little name / by chance his girlfriend came across the needle and soon she did the same.” This song follows a couplet rhyming scheme with clear end rhymes.

- The indie rock band The National use a ABCB rhyme scheme in their song “Conversation 16”: “I think the kids are in trouble / I do not know what all the troubles are for. / Give them ice for their fevers, / You’re the only thing I ever want anymore.”

- Jay-Z’s song “Renegade” plays with internal rhyme in the line “Hiding down ducking strays from frustrated youth stuck in they ways.”

Examples in Literature

1. William Shakespeare, The Tempest

In Act I, Scene II of this play, the spirit Ariel sings to the shipwrecked Ferdinand:

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell

Hark! Now I hear them—Ding-dong, bell.

Ariel’s song follows a ABABCCDD rhyme scheme. The musicality of his song is emphasized by the rhymes, and the fluidity of the rhyme scheme matches Ariel’s unpredictable supernatural nature.

2. Eve L. Ewing, “Jump / Rope”

In Ewing’s powerful poem, she makes use of childhood jump rope rhymes to tell the story of a young black man who was murdered by a group of white youths at a beach in Chicago in 1919:

Little Eugene Gene Gene

Sweetest I’ve ever seen seen seen

His mama told him him

Them white boys mean mean mean

The comforting repetition of end rhymes and the sing-song elements of Ewing’s AABA rhyme scheme serve as a stark contrast to the violence the poem describes. In the penultimate stanza, Ewing relies on the reader’s anticipation of rhyme to imply the tragic end:

Grandma Grandma sick in bed

Call on Jesus cause your baby’s

Ewing leaves a blank space on the page so that the readers must fill in the word dead for themselves.

3. Elizabeth Bishop, “One Art”

In the opening stanza of her poem, Bishop declares:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

This poem is a villanelle—a French verse form consisting of five tercets and a final quatrain (four-line stanza). This form requires that the first and third line of the first stanza must rhyme.

4. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”

In Part 2 of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” the Mariner confesses:

And I had done a hellish thing,

And it would work ‘em woe.

For all averred I had killed the bird

That made the breeze to blow.

Here, the Mariner is explaining how his former shipmates responded to his “hellish” act of killing the albatross, which will later doom them. These lines of the poem contain both end rhymes (woe and blow) as well as an internal rhyme of (averred with bird).

5. Terrance Hayes, “The Blue Kool”

In Hayes’s second book, Wind in a Box, he writes a series of dramatic monologues. These poems are written from the point of view of a character, rather than the poet’s own personal experience. In this poem, Hayes speaks in the voice of the pioneering rapper Kool Keith:

…You penny-loafer.

I got a chauffeur

Although Hayes very rarely rhymes in his other poems, here he uses end rhymes to help establish the character of his speaker. Because Kool Keith was one of the first rappers, it makes perfect sense that he would speak in rhyme in Hayes’s poem.

Further Resources on Rhyme

The Guardian has an excellent article about the power of rhyming verse in theater.

Rhymer is a free online rhyming dictionary with a comprehensive database of rhyming words.

Poet Patrick Gillespie wrote an analysis of contemporary poetry’s movement away from rhyme.