meter

What Is Meter? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Meter Definition

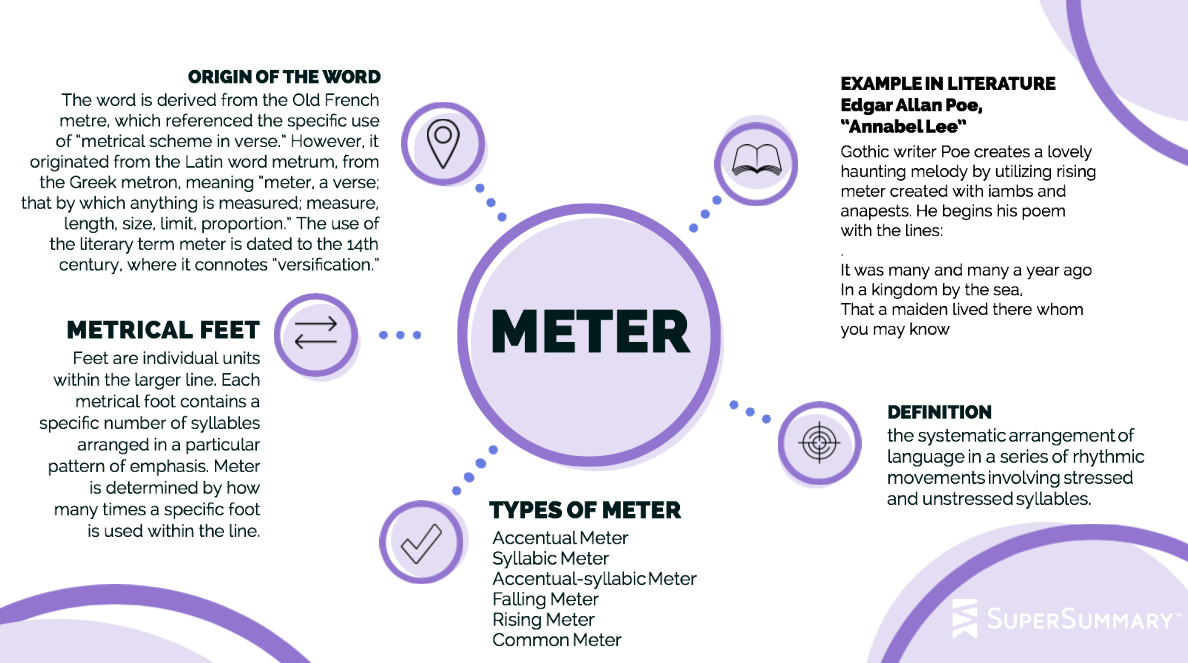

Meter (mee-ter) is the systematic arrangement of language in a series of rhythmic movements involving stressed and unstressed syllables. It is a poetic measure related to the length and rhythm of the poetic line.

The word is derived from the Old French metre, which referenced the specific use of “metrical scheme in verse.” However, it originated from the Latin word metrum, from the Greek metron, meaning “meter, a verse; that by which anything is measured; measure, length, size, limit, proportion.” The use of the literary term meter is dated to the 14th century, where it connotes “versification.”

The Components of Meter

While a poem can be structured in different ways, meter is one of the most fundamental. It is the rhythmic pattern of a line within formal verse and blank verse poetry. The two basic components of meter are the number of syllables in a line and the pattern of emphasis (stressed or unstressed) that these syllables are arranged in.

Stressed syllables are emphasized, while unstressed syllables are not. For example, with the word atom, the first syllable is emphasized, and the second syllable is not. When spoken, the word makes a sound like “DUM-da.” This is different from a word like display, where the second syllable is stressed, and the pattern of emphasis sounds more like “da-DUM.”

Metrical Feet

When people discuss metrical patterns in verse, they often refer to feet. Feet are individual units within the larger line. Each metrical foot contains a specific number of syllables arranged in a particular pattern of emphasis. Meter is determined by how many times a specific foot is used within the line.

Common Types of Metrical Feet

- Iambs are made up of two syllables in a pattern of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable: the words amuse, portray, and return.

- Trochees are made up of two syllables in a pattern of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable: the words happy, clever, and planet.

- Spondees are made up of two stressed syllables: the words heartbreak, shortcake, and bathrobe.

- Dactyls are made up of three syllables in a pattern of one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables: the words merrily, buffalo, and scorpion.

- Anapests are made up of three syllables in a pattern of two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable: the words understand, interrupt, and the word anapest

Describing Lines of Verse with Meter

To name the meter of a verse, one generally combines the name of the metrical foot and the number of stress patterns per line, named based on Greek numerals (mono– for one, di– for two, tri– for three, and so on). For example, a line of five iambs would be called iambic pentameter, while a line made up of six dactyls would be called dactylic hexameter.

Monometer

Lines in monometer are comprised of a single metrical foot. Monometer is rarely used, but Robert Herrick’s poem “Upon His Departure Hence” is an example that uses iambic monometer: “Thus I / Pass by / And die.”

Dimeter

Lines in dimeter contain two metrical feet. Muriel Rukeyser uses iambic dimeter throughout her poem “Yes”:

What can it mean?

It’s just like life,

One thing to you

One to your wife.

Trimeter

Lines in trimeter are composed of three metrical feet. In addition to verse, many advertising slogans are written in trimeter. For example, the United States Army’s slogan, “Be all that you can be” is written in iambic trimeter.

Tetrameter

Lines in tetrameter consist of four metrical feet. Shakespeare sometimes wrote in trochaic tetrameter, like in this excerpt from

“The Phoenix and the Turtle”:

Reason, in itself confounded,

Saw division grow together,

To themselves yet either neither,

Simple were so well compounded

Pentameter

Lines in pentameter contain five metrical feet. Iambic pentameter is perhaps the most familiar meter in English verse; it was used by William Shakespeare, John Donne, and Geoffrey Chaucer. The famous opening to Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales is written in iambic pentameter: “Whan that aprill with his shoures soote / The droghte of march hath perced to the roote.” (Don’t forget that Chaucer wrote in Middle English, so the pronunciation—as well as spelling—of some words varied from what we are used to today.)

Hexameter

Lines in hexameter consist of six feet. This was the primary meter used in classical Greek and Latin literature, including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, Horace’s Satires, and Ovid’s Metamorphosis.

In English literature, a line in iambic hexameter is also called an alexandrine. Each stanza in Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Convergence of the Twain” ends with an alexandrine: “Cold currents third, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres” in Stanza II, “Lie lightless, all their sparkles bleared and black and blind” in Stanza IV, and “A Shape of Ice, for the time far and dissociate” in Stanza VII.

Types of Meter

While there are many different types of meter, the following are some of the most common.

Accentual Meter

Accentual meter has a set count of stresses per line regardless of how many syllables are present. This is most common in children’s poetry, nursery rhymes, and the chants that accompany many jump rope games. Consider the children’s rhyme “Star Light, Star Bright”:

Star light, Star bright /

First star I see tonight /

I wish I may, I wish I might /

Have the wish I wish tonight

Each line contains four stresses, but the total syllabic count varies. Line one has four syllables, line two has six, line three has eight, and line four has seven. Despite the shifting syllabic count, the meter remains strong with four beats per line.

Syllabic Meter

This is a metrical pattern determined by a set count of syllables, rather than the amount of stresses. The Japanese haiku is an example of syllabic meter. It consists of a tercet (three-line poem) with the first line containing five syllables, the second line containing seven syllables, and the final line returning to the five-syllable count. Where the stress falls is irrelevant to the form since the form itself is determined by the number of syllables in the line.

This haiku by Japanese poet Matsuo Basho is an example of syllabic meter:

An old silent pond…

A frog jumps into the pond,

splash! Silence again.

Accentual-Syllabic Meter

In accentual-syllabic meter, both the number of syllables and the number of stresses are consistent. Up until the advent of free verse, this was the most common meter used in English verse. Consider these lines from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade”:

Cannon to right of them

Cannon to left of them

Cannon in front of them

Tennyson composed these lines using dactylic dimeter. Each line has six syllables, and the syllables follow the pattern of stressed-unstressed-unstressed twice per line.

Falling Meter

This type of meter is written in trochees and dactyls, which have a stressed syllable followed by one or two unstressed syllables. Therefore, the meter “falls” from stressed to unstressed. The children’s rhyme “Peter, Peter, pumpkin-eater” is an example of falling meter.

Rising meter

This type utilizes iambs and anapests, which begin with one or two unstressed syllables and end with a stressed syllable. Thus, the meter “rises” from unstressed to stressed emphasis. For example, consider the following lines from William Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 29”: “When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes / I all alone beweep my outcast state.”

Common meter

Verse in common meter consists of four lines that alternate between iambic tetrameter (four iambs per line) and iambic trimester (three iambs per line). Common meter is used not only in poetry but also in pop songs like “Stairway to Heaven,” TV show theme songs like the “Gilligan’s Island” theme, folk songs like “The House of the Rising Sun,” and hymns like “Amazing Grace.”

Why Writers Use Meter

Meter adds rhythm and order to writers’ work, giving verse a pleasant melodious sound. It also unconsciously engages readers as they begin to anticipate the metrical pattern and read in rhythm, thus lending a hypnotic effect to the verse.

Meter also determines what type of verse is being written: formal, blank, or free. Depending on the type of verse, the writer’s choice of metrical pattern may be further regulated by the rules of a specific type of poetic form.

Meter in Verse

Many poems and plays written in verse adhere to certain set metric patterns. While meter is often paired with rhyme, it does not need to be. There are three different categories that verse can be placed in when thinking about meter:

- Free verse is a type of poetry that does not contain any set meter or rhyme scheme.

- Formal verse has a strict meter and rhyme scheme; for example, sonnets or haiku.

- Blank verse does not have a rhyme scheme but does adhere to a strict meter.

Poetry and plays written in verse can maintain the same meter throughout or change meter in different sections. When analyzing meter, focus on meter within the work as a whole or within a stanza or line. The study of versification, especially the study of metrical structure, is called prosody.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Meter

Poetry in English is based on qualitative meter, which refers to patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables occurring at regularly determined intervals within the poetic line. In classical Greek, classical Latin, classical Arabic, and Sanskrit poetry, however, meter was not dictated by syllabic stress. Instead, it was determined by syllabic weight. Syllabic weight indicates the length of the syllable in terms of pronunciation. For example, a long syllable literally takes longer to pronounce than a short syllable. This type of meter is called quantitative meter. In quantitative meter, the stress patterns of words have no effect on the meter whatsoever. It is rare to encounter quantitative meter in poetry written in English.

Examples of Meter in Literature

1. William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

In this romantic comedy, Shakespeare’s noble characters speak in iambic pentameter to differentiate them from the plainer and less melodious speech of the working class. For example, in Act 1, Scene 1, Theseus says:

Now, fair Hippolyta, our nuptial hour

Draws on apace. Four happy days bring in

Another moon. But oh, methinks how slow

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires,

Like to a stepdame or a dowager

Long withering out a young man’s revenue.

2. Edgar Allan Poe, “Annabel Lee”

Gothic writer Poe creates a lovely haunting melody by utilizing rising meter created with iambs and anapests. He begins his poem with the lines:

It was many and many a year ago

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden lived there whom you may know

The first line contains three anapests and an iamb, which makes it an anapestic tetrameter. The second line is an iambic trimeter because it opens with an anapest but concludes with two iambic feet. The third line is another tetrameter, but here it is equally comprised of anapests and iambs, making it a split line.

3. Emily Dickinson, “Because I could not stop for Death (479)”

Dickinson composed her poems primarily in common meter, similar to hymns and ballads of her day. Here she alternates between iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter. In the first stanza of this famous poem, Dickinson writes:

Because I could not stop for Death—

He kindly stopped for me—

The Carriage held but just Ourselves—

And Immortality.

Dickinson’s use of these metrical patterns lends a lovely musical quality to her poems.

4. Marilyn Nelson, “Chosen”

Although most contemporary poets write in free verse, others still work within traditional frameworks of meter. In this sonnet, Nelson describes the relationship between her enslaved great-great grandmother Diverne and Diverne’s white master. The poem opens:

Diverne wanted to die that August night.

His face hung over hers, a sweating moon.

She wished so hard she killed part of her heart.

The formal and musical qualities lent to the poem by Nelson’s use of iambic pentameter stand in contrast to the distressing scene portrayed. This tension between form and content adds additional depth and power to Nelson’s work.

Further Resources on Meter

This wonderful guide from Earlham College shows how to apply poetic metric ideas to musical rhythms.

Author and poet Dusty Green wrote a breakdown of meter and metrical patterns for The Society of Classical Poets.

Frontiers in Psychology: Language Sciences published very interesting research into the aesthetics and emotional effects of meter and rhyme in poetry.

The University of Pennsylvania has an insightful and concise guide to meter as a supplement to one of their courses in English literature.