irony

What Is Irony? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Irony Definition

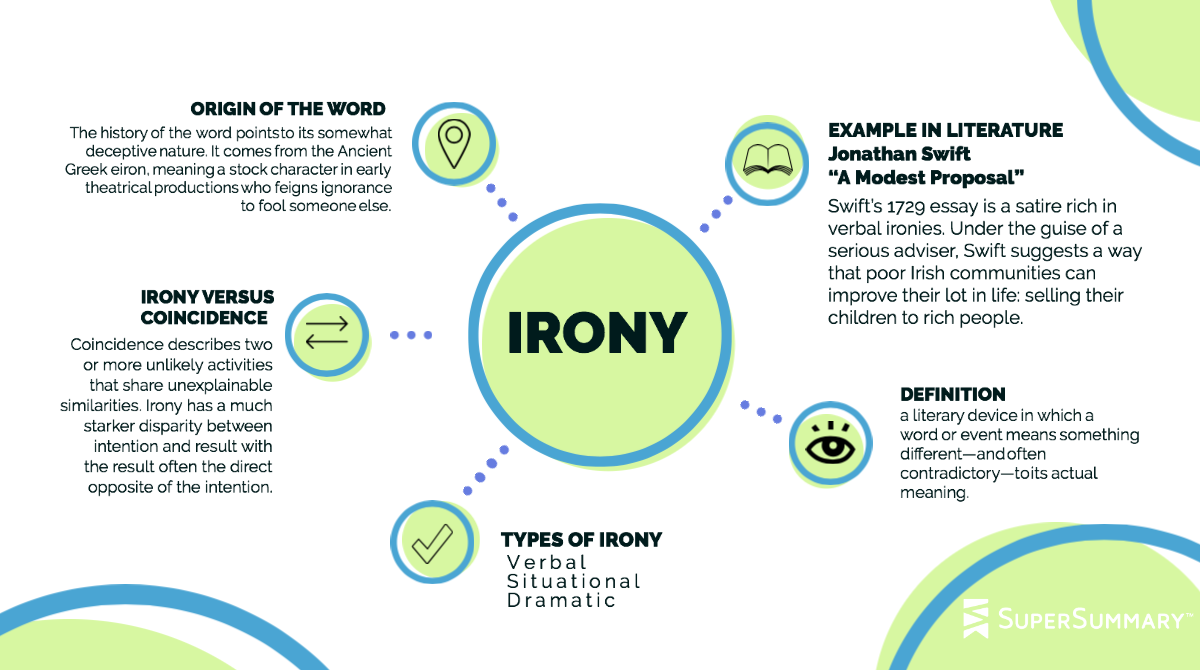

Irony (EYE-run-ee) is a literary device in which a word or event means something different—and often contradictory—to its actual meaning. At its most fundamental, irony is a difference between reality and something’s appearance or expectation, creating a natural tension when presented in the context of a story. In recent years, irony has taken on an additional meaning, referring to a situation or joke that is subversive in nature; the fact that the term has come to mean something different than what it actually does is, in itself, ironic.

The history of the word points to its somewhat deceptive nature. It comes from the Ancient Greek eiron, meaning a stock character in early theatrical productions who feigns ignorance to fool someone else.

Types of Irony

When someone uses irony, it is typically in one of the three ways: verbal, situational, or dramatic.

Verbal Irony

In this form of irony, the speaker says something that differs from—and is usually in opposition with—the real meaning of the word(s) they’ve used. Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Cask of Amontillado.” As Montresor encloses Fortunato into the catacombs’ walls, he mocks Fortunato’s plea—”For the love of God, Montresor!”—by replying, “Yes, for the love of God!” Poe uses this to underscore how Montresor’s actions are anything but loving or humane—thus, far from God.

Situational Irony

This occurs when there is a difference between the intention of a specific situation and its result. The result is often unexpected or contrary to a person’s goal. The entire plot of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz hinges on situational irony. Dorothy and her friends spend the story trying to reach the Wizard so Dorothy can find a way back home, but in the end, the Wizard informs her that she had the power and knowledge to return home all along.

Dramatic Irony

Here, there is a disparity in how a character understands a situation and how the audience understands it. In Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House, the married Nora excitedly anticipates the day when she’ll be able to repay Krogstad, who illegally lent her money. She imagines a future “free from care,” but the audience understands that, because Nora must continue to lie to her husband about the loan, she will never be free.

Not all irony adheres perfectly to one of these definitions. In some cases, irony is simply irony, where something’s appearance on the surface is substantially different from the truth.

Irony vs. Coincidence

Irony is often confused with coincidence. Though there is some overlap between the two terms, they are not the same thing. Coincidence describes two or more unlikely activities that share unexplainable similarities. It is often confused with situational irony. For example, finding out a friend you made in adulthood went to your high school is a coincidence, not an ironic event. Additionally, coincidence isn’t classifiable by type.

Irony, on the other hand, has a much starker and more substantial disparity between intention and result, with the result often the direct opposite of the intention. For example, the fact that the word lisp is ironic, considering it refers to an inability to properly pronounce s sounds but itself contains an s.

The Functions of Irony

How an author uses irony depends on their intentions and the story or scene’s larger context. In much of literature, irony highlights a larger point the author is making—often a commentary on the inherent difficulties and messiness of human existence.

With verbal irony, a writer can demonstrate a character’s intelligence, wit, or snark—or, as in the case of “The Cask of Amontillado,” a character’s unmitigated evil. It is primarily used in dialogue and rarely offers up any insight into the plot or meaning of a story.

With dramatic irony, a writer illustrates that knowledge is always a work in progress. It reiterates that people rarely have all the answers in life and can easily be wrong when they don’t have the right information. By giving readers knowledge the characters do not have, dramatic irony keeps readers engaged in the story; they want to see if and when the characters learn this information.

Finally, situational irony is a statement on how random and unpredictable life can be. It showcases how things can change in the blink of an eye and in bigger ways than one ever anticipated. It also points out how humans are at the mercy of unexplained forces, be they spiritual, rational, or matters of pure chance.

Irony as a Function of Sarcasm and Satire

Satire and sarcasm often utilize irony to amplify the point made by the speaker.

Sarcasm is a rancorous or stinging expression that disparages or taunts its subject. Thus, it usually possesses a certain amount of irony. Because inflection conveys sarcasm more clearly, saying a sarcastic remark out loud helps make the true meaning known. If someone says “Boy, the weather sure is beautiful today” when it is dark and storming, they’re making a sarcastic remark. This statement is also an example of verbal irony because the speaker is saying something in direct opposition to reality. But an expression doesn’t necessarily need to be verbal to communicate its sarcastic nature. If the previous example appeared in a written work, the application of italics would emphasize to the reader that the speaker’s use of the word beautiful is suspect. To further clarify, the remark would closely precede or follow a description of the day’s unappealing weather.

Satire is an entire work that critiques the behavior of specific individuals, institutions, or societies through outsized humor. Satire normally possesses both irony and sarcasm to further underscore the illogicality or ridiculousness of the targeted subject. Satire has a long history in literature and popular culture. The first known satirical work, “The Satire of the Trades,” dates back to the second millennium BCE. It discusses a variety of trades in an exaggerated, negative light, while presenting the trade of writer as one of great honor and nobility. Shakespeare famously satirized the cultural and societal norms of his time in many of his plays. In 21st-century pop culture, The Colbert Report was a political satire show, in which host Stephen Colbert played an over-the-top conservative political commentator. By embodying the characteristics—including vocal qualities—and beliefs of a stereotypical pundit, Colbert skewered political norms through abundant use of verbal irony. This is also an example of situational irony, as the audience knew Colbert, in reality, disagreed with the kind of ideas he was espousing.

Uses of Irony in Popular Culture

Popular culture has countless examples of irony.

One of the most predominant, contemporary references, Alanis Morissette’s hit song “Ironic” generated much controversy and debate around what, exactly, constitutes irony. In the song, Morissette sings about a variety of unfortunate situations, like rainy weather on the day of a wedding, finding a fly floating in a class of wine, and a death row inmate being pardoned minutes after they were killed. Morissette follows these lines with the question, “Isn’t it ironic?” In reality, none of these situations is ironic, at least not according to the traditional meaning of the word. These situations are coincidental, frustrating, or plain bad luck, but they aren’t ironic. The intended meaning of these examples is not disparate from their actual meanings. For instance, another line claims that having “ten thousand spoons when all you need is a knife” is ironic. This would only be ironic, if, say, the person being addressed made knives for a living. Morissette herself has acknowledged the debate and asserted that the song itself is ironic because none of the things she sings about are ironic at all.

Pixar/Disney’s movie Monsters, Inc. is an example of situational irony. In the world of this movie, monsters go into the human realm to scare children and harvest their screams. But, when a little girl enters the monster world, it’s revealed that the monsters are actually terrified of children. There are also moments of dramatic irony. As protagonist Sully and Mike try to hide the girl’s presence, she instigates many mishaps that amuse the audience because they know she’s there but other characters have no idea.

In the iconic television show Breaking Bad, DEA agent Hank Schrader hunts for the elusive drug kingpin known as Heisenberg. But what Hank doesn’t know is that Heisenberg is really Walter White, Hank’s brother-in-law. This is a perfect example of dramatic irony because the viewers are aware of Walter’s secret identity from the moment he adopts it.

Examples of Irony in Literature

1. Jonathan Swift, “A Modest Proposal”

Swift’s 1729 essay is a satire rich in verbal ironies. Under the guise of a serious adviser, Swift suggests a way that poor Irish communities can improve their lot in life: selling their children to rich people. He even goes a step further with his advice:

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout.

Obviously, Swift does not intend for anyone to sell or eat children. He uses verbal ironies to illuminate class divisions, specifically many Britons’ attitudes toward the Irish and the way the wealthy disregard the needs of the poor.

2. William Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus

This epic Shakespeare tragedy is brutal, bloody, farcical, and dramatically ironic. It concerns the savage revenge exacted by General Titus on those who wronged him. His plans for revenge involve Tamora, Queen of the Goths, who is exacting her own vengeance for the wrongs she feels her sons have suffered. The audience knows from the outset what these characters previously endured and thus understand the true motivations of Titus and Tamora.

In perhaps the most famous scene, and likely one of literature’s most wicked dramatic ironies, Titus slays Tamora’s two cherished sons, grinds them up, and bakes them into a pie. He then serves the pie to Tamora and all the guests attending a feast at his house. After revealing the truth, Titus kills Tamora—then the emperor’s son, Saturninus, kills Titus, then Titus’s son Lucius kills Saturninus and so on.

3. O. Henry, “The Gift of the Magi”

In this short story, a young married couple is strapped for money and tries to come up with acceptable Christmas gifts to exchange. Della, the wife, sells her hair to get the money to buy her husband Jim a watchband. Jim, however, sells his watch to buy Della a set of combs. This is a poignant instance of situational irony, the meaning of which O. Henry accentuates by writing that, although “[e]ach sold the most valuable thing he owned in order to buy a gift for the other,” they were truly “the wise ones.” That final phrase compares the couple to the biblical Magi who brought gifts to baby Jesus, whose birthday anecdotally falls on Christmas Day.

4. Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

Atwood’s dystopian novel takes place in a not-too-distant America. Now known as Gilead, it is an isolated and insular country run by a theocratic government. Since an epidemic left many women infertile, the government enslaves those still able to conceive and assigns them as handmaids to carry children for rich and powerful men. If a handmaid and a Commander conceive, the handmaid must give the child over to the care of the Commander and his wife. Then, the handmaid is reassigned to another “post.”

A primary character in the story is Serena Joy, a Commander’s wife. In one of the book’s many ironic instances, it is revealed that Serena, in her pre-Gilead days, was a fierce advocate for a more conservative society. Though she now has the society she fought for, women—even Commanders’ wives—have few rights. Thus, she ironically suffers from the very reforms she spearheaded.

Further Resources on Irony

The Writer has an article about writing and understanding irony in fiction.

Penlighten‘s detailed list of irony examples includes works mainly from classic literature.

Publishing Crawl offers five ways to incorporate dramatic irony into your writing.

Harvard Library has an in-depth breakdown of the evolution of irony in postmodern literature.

TV Tropes is a comprehensive resource for irony in everything from literature and anime to television and movies.