rhythm

What Is Rhythm? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Rhythm Definition

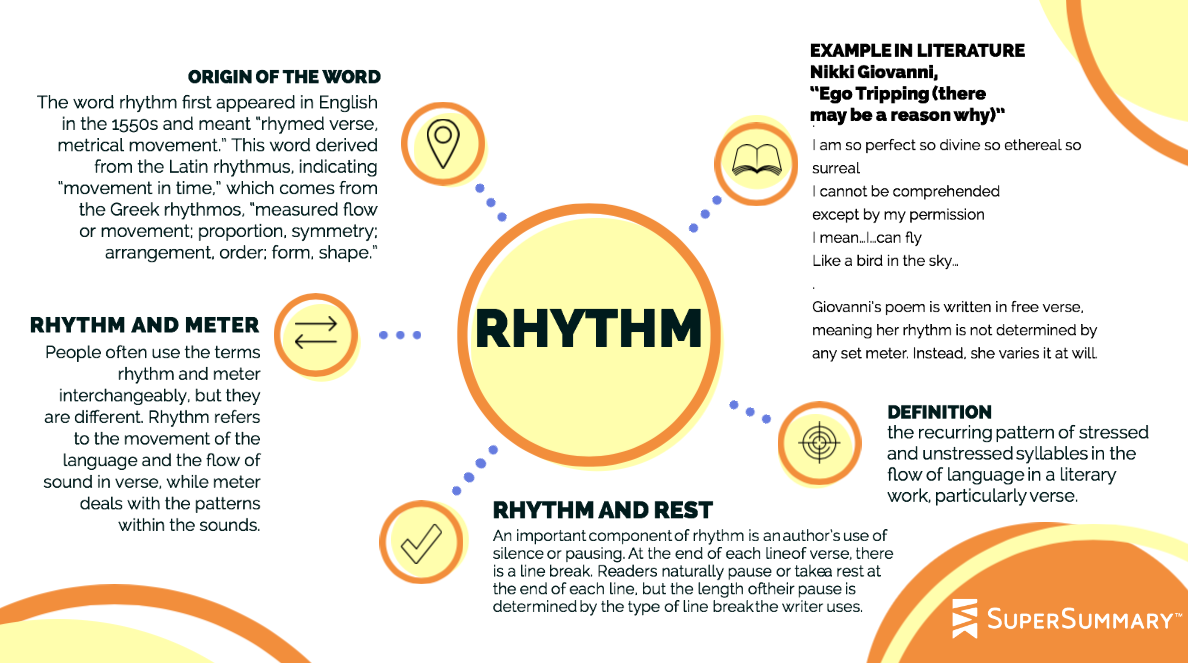

Rhythm (RIH-thum) is the recurring pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in the flow of language in a literary work, particularly verse. Rhythm is best understood as the pace and beat of a poem, and it’s created through specific variations of syllabic emphasis.

The word rhythm first appeared in English in the 1550s and meant “rhymed verse, metrical movement.” This word derived from the Latin rhythmus, indicating “movement in time,” which comes from the Greek rhythmos, “measured flow or movement; proportion, symmetry; arrangement, order; form, shape.”

The Elements of Rhythm

Rhythm is the flow of sound within a literary work. This movement of language is primarily created through diction (the author’s choice of words) and syntax, which is how the writer chooses to arrange those words. Other literary devices—such as meter, rhyme, refrain, enjambment, caesuras, and end-stops—also contribute to rhythm, although they are optional components.

Rhythm and Meter

Rhythm in verse is closely linked to meter. People often use the terms rhythm and meter interchangeably, but they’re different. Rhythm refers to the movement of the language and the flow of sound in verse, while meter deals with the patterns within the sounds.

Meter refers to the number of syllables in a poetic line and the pattern of emphasis (stressed or unstressed) that these syllables are arranged in. There are five basic patterns of syllabic emphasis in English verse.

- Iambs consist of two syllables—an unstressed syllable and then a stressed syllable. The words amuse, portray, and return are iambs.

- Trochees are the reverse of iambs. They consist of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable. The words happy, clever, and planet are examples of trochees.

- Spondees are two consecutive stressed syllables, like in the words heartbreak, shortcake, and bathrobe.

- Dactyls are three syllable units in a stressed-unstressed-unstressed configuration—for example, the words merrily, buffalo, and scorpion.

- Anapests consist of three syllable units that follow an unstressed-unstressed-stressed pattern. Understand, interrupt, and the word anapest itself are anapests.

These types of syllabic emphasis are called feet, which are individual units within the larger poetic line. A line’s meter is determined by the type of metrical foot used and how often it appears in the line. For example, a line written in iambic pentameter is a line consisting of five iambs.

Metrical patterns can contribute to a pleasing rhythm, but they’re not necessary for rhythm to exist. Free verse poetry, for instance, doesn’t follow any set metrical patterns and still has rhythm. But while rhythm can exist without meter, meter is often a component of rhythm.

Rhythm and Rhyme

Rhyme is an important component of rhythm, but—like meter—it’s not required for rhythm to exist. Rhyme is the repetition of similar sounds, particularly at the end of words; “The cat sat on a blue mat.” Set patterns of rhyme within different types of poetry or verse are referred to as rhyme schemes. As with meter, rhyme schemes can help create a pleasing and predictable pattern of sound that augments a work’s rhythm. However, rhythm can occur without them, as it does in free verse poetry and blank verse.

Rhythm and Rest

Another important component of rhythm is an author’s use of silence or pausing. At the end of each line of verse, there’s a line break. Readers naturally pause or take a rest at the end of each line, but the length of their pause is determined by the type of line break the writer uses.

There are two types of line breaks: enjambments and end-stopped lines.

- Enjambments happen when the line of verse breaks somewhere inside a clause or sentence. Enjambed lines create short pauses as the reader unconsciously speeds up to get to the next line so they can understand the full unit of meaning when the clause or sentence ends.

- End-stopped lines occur with complete grammatical units. This doesn’t need to be a full sentence, but the line must end with a punctuation mark indicating that the grammatical unit of meaning has finished (i.e., period, semi-colon, closing parenthesis, comma, etc.). Readers pause for longer at end-stopped lines as the punctuation mark indicates a sense of completion.

Pauses can also be created by white space, a poetic tool wherein an author may have extra space inside a line rather than words. For example, in “From the Devotions,” Carl Philips writes: “usual or masterable way leaves, a woman’s.” This white space creates a pause inside the middle of the line. White space can be considered a visual manifestation of a caesura, which is a pause in the middle of the line.

The pauses created by line breaks and white space are a crucial element of the rhythm, or flow of sound, of the literary work.

The Effects of Rhythm

Writers use rhythm to create several different effects. Rhythmical patterns create a kind of literary music, soothing and pleasing the audience. These patterns also hold a reader’s attention as they become unconsciously ensnared in the rhythm, encouraging them to read further. The stressed and unstressed syllables also allow authors to place additional emphasis on certain words, creating a more powerful semantic effect. Rhythmic patterns also help readers memorize poems more easily for recitation. Sometimes authors may use specific rhythms to amplify a poem’s subject matter or meaning.

Rhythm and Music

Rhythm is an important aspect of enjoying music. Any time someone nods their head, taps their feet, or snaps their fingers along with the beat of a song, they are experiencing that song’s rhythm. These reactions occur because rhythmic sound meshes with the brain circuits that control emotion and movement. According to research by psychologist Annett Schirmer, “Within a few measures of music your brain waves start to get in synch with the rhythm.”

While individual songs can follow any rhythm, most genres adhere to specific rhythmic elements. For instance, hip-hop tends to have a tempo range of 85-115 beats per minute, while rock stays in a 110-140 beats per minute range, and R&B is at a slower 60-80 beats per minute. These different tempos, along with the drumbeat emphasis (which also varies by genre), contribute to different effects on the listener. The slower R&B tempo, for example, is more romantic and calming, while the faster rock tempo generates more adrenaline.

Examples of Rhythm in Poetry

1. Rupert Brooke, “The Soldier”

Brooke frequently wrote patriotic poetry about England. His most famous poem, “The Solider,” opens with his speaker stating:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed

Brooke uses the bouncing beat of iambic pentameter to conjure up the rhythm of soldiers marching. This rhythm also lulls the reader, contributing to the way the poem positively explores the possibility of dying for one’s country, rather than dwelling on death as a source of pain.

2. Nikki Giovanni, “Ego Tripping (there may be a reason why)”

Giovanni is known for poetry that often celebrates being a black woman. In the last two stanzas of this poem, she says:

I am so perfect so divine so ethereal so surreal

I cannot be comprehended

except by my permission

I mean…I…can fly

Like a bird in the sky…

Giovanni’s poem is written in free verse, meaning her rhythm is not determined by any set meter. Instead, she varies it at will. She uses a run-on sentence without any punctuation to create a litany of self-affirmation ending in an eye rhyme. Giovanni also creates momentum through enjambment between lines and ellipses in the penultimate line to create caesuras between the words. This poem’s rhythm gives it an ebullient flow that matches her enthusiasm and joyful self-confidence.

3. Edgar Allan Poe, “Annabel Lee”

In the opening stanza, Poe’s speaker begins the story of his love for a long-dead maiden:

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

This poem has a sing-song sort of rhythm, which Poe creates by alternating anapests and iambs. Each line begins with an anapest that is followed by either another anapest or an iamb. These alternating patterns of unstressed and stressed syllables give the poem a melodious and pleasing sound.

4. Wendy Xu, “And Then It Was Less Bleak Because We Said So”

Wendy Xu opens her poem by saying:

Today there has been so much talk of things exploding

into other things, so much that we all become curious, that we

all run outside into the hot streets

and hug. Romance is a grotto of eager stones

Xu’s poem is free verse, so it does’t follow any set metrical pattern, and it does not rhyme. Her rhythm comes from the flow of natural speech patterns instead. This poem has a breathless momentum to it that is created through Xu’s use of enjambment. The entire 15-line poem is written with enjambed lines and only utilizes an end stop in the final line. This technique makes her poem fast paced, and the final line, with its period, gives the reader a strong sense of completion and rest.

Further Resources on Rhythm

Edward Hirsch wrote a fascinating essay about rhythm for The Poetry Foundation.

Poet Ellen Bryant Voight wrote a wonderful book about syntax in poetry and its effect on rhythm and meaning.

Timothy Steele analyzed the prevalence of free verse rhythm rather than meter in contemporary poetry for The Academy of American Poets.