prosody

What Is Prosody? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Prosody Definition

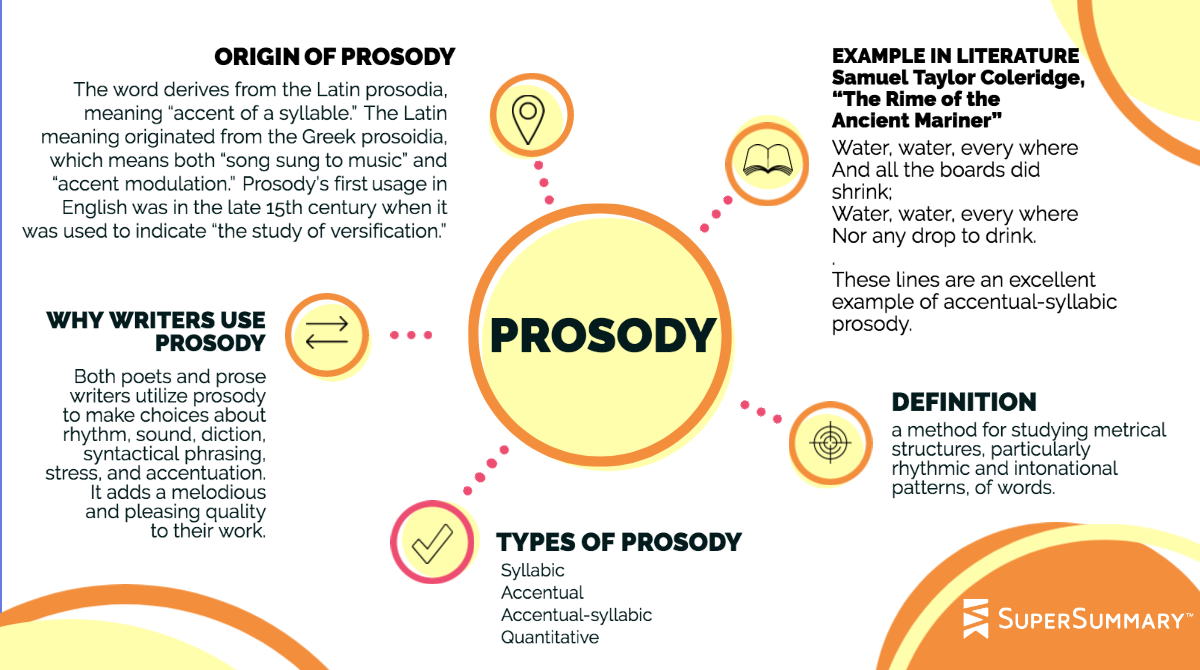

Prosody (PROHZ-o-dee) is a method for studying metrical structures, particularly rhythmic and intonational patterns, of words. Prosody is generally discussed in the context of poetry, although it is also utilized, to a lesser extent, in prose.

The word derives from the Latin prosodia, meaning “accent of a syllable.” The Latin meaning originated from the Greek prosoidia, which means both “song sung to music” and “accent modulation.” The originating Greek word is formed from pros, meaning “to, near, forward,” combined with oide, which means “song” or “poem.” Prosody’s first usage in English was in the late 15th century, when it was used to indicate “the study of versification.”

Different Types of Prosody

There are four specific prosodic metrical patterns used for analyzing verse.

Syllabic Prosody

This style of analysis focuses on a fixed number of syllables in each line, independent of the stressed or unstressed emphasis. Syllabic prosody is particularly useful when studying poetic forms like the Japanese haiku or tanka.

Accentual Prosody

Unlike syllabic prosody, accentual prosody does not measure the number of syllables per line. It counts the number of stresses or accents each line contains. This type of prosody is particularly relevant for Germanic or Old English poetry.

Accentual-Syllabic Prosody

This type of prosody measures both the number of syllables and the patterns of emphasis in each line of verse. It is very commonly used in the analysis of English poetry and theatrical verse.

Quantitative Prosody

Rather than counting the number of syllables or stresses per line, quantitative prosody is concerned with the length (duration) or shortness of the syllables’ pronunciation. This type of prosody is most relevant for studying classical Greek and Roman poetry; it very rarely applies to English poetry.

Prosody as a Linguistic Technique

While prosody is commonly considered a method for analyzing verse, it also is an important phonetics term. In linguistics, prosody is used to analyze suprasegmentals—elements of speech larger than the individual segments of consonants and vowels. This means that, in addition to syllables, linguistic prosody concerns itself with tone, stress, rhythm, intonation, and chunking (the perception of word groups or chunks based on pausing).

Linguistic prosody can also be used to analyze a speaker, including their emotional state and what they’re saying. When analyzing speech, linguistic prosody often focuses on whether irony or sarcasm is intended; where emphasis is placed; whether what is spoken is intended as a statement, a command, or a question; and other elements of language not indicated by diction or syntax.

Finally, linguistic prosody distinguishes between auditory variables—subjective impressions experienced by the listener—and acoustic variables—the objectively measurable properties of sound waves. Auditory variables include the pitch of a voice, sound length, loudness or softness, and timbre (sound quality). Rhythm, tempo, and pausing are also important elements of linguistic prosody.

Why Writers Use Prosody

Writers incorporate metrical structures and patterns of intonation—the elements of prosody—into their work to add melody, rhythm, and order and, at times, work purposefully against those patterns to create emotional and aesthetic effects. Both poets and prose writers utilize prosody to make choices about rhythm, sound, diction, syntactical phrasing, stress, and accentuation. It adds a melodious and pleasing quality to their work.

How Prosody Affects Literary Analysis

Readers and scholars utilize prosody to better understand the choices writers make. Analyzing how a line of verse or a poem is put together, syllable by syllable, allows readers to see how the work is constructed and fluently articulate why the writer chose to employ or break their metrical patterns in certain moments. Prosody gives readers greater insight into the details of how a literary work is put together so they can gain new understanding and appreciation for how it functions.

Prosody in Poetry

For poetry and other works written in verse, prosody means the analysis of metrical patterns of rhythm and intonation. Prosody makes use of scansion, which is the act of dividing lines of verse into metrical feet. These feet are discrete units categorized by the number and location of the accented and unaccented syllables. Scansion analyzes the verse’s meter based on the number of feet per line and the patterns the accented syllables take.

While prosody is primarily concerned with the study of meter, modern criticism has expanded it to incorporate what poet and critic Ezra Pound called “the articulation of the total sound of the poem.” This wider scope of prosody means that prosody also incorporates analyzing other elements of sound, pace (or tempo), and meaning.

Some of the additional elements of sound employed by prosody are consonance, alliteration, assonance, and rhyme.

- Consonance indicates repetitive sounds produced by consonants in words or phrases. Consonant sounds generally occur at the end of a word, but they can also occur in the middle. Consonance occurs in closely connected, adjacent, or consecutive words. For example, the words pitter patter or the repetition of the g and the r sounds in the phrase “Tyger, Tyger, burning bright” from William Blake’s famous poem “The Tyger.”

- Alliteration, which is a type of consonance, is the repetition of the same letter or sound, usually initial consonant sounds, in two or more neighboring words or syllables. For example, the nursery rhyme “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers” contains a repeated p sound at the beginning of most words, and the store Bed, Bath & Beyond uses repeated b. Alliteration is also called initial rhyme or head rhyme.

- Assonance means the relatively close appearance of the same vowels or of similar sounds, particularly vowels. For example, the words holy and phony or the lines “Those images that yet / Fresh images beget / That dolphin-torn, that gong-tormented sea” in William Butler Yeats’s poem “Byzantium.”

- Rhyme is the correspondence of sound between words or the ending of words. It is often present in poetry and songs. For example, Shakespeare’s sonnets employ rhyming words in a specific pattern at the end of each line. In “Sonnet 18,” day and May in lines 1 and 3, and temperate and date in lines 2 and 4, are rhyming pairs; though in the second example, temperate must be pronounced with a long vowel sound in the final syllable to perfectly rhyme with date.

Prosody in Other Contexts

Prosody in Speech

Various components of prosody, such as intonation, rhythm, and stress, provide important information about speech that goes beyond the literal meaning of words. For instance, the sentence “Yeah, I really love her” can mean very different things depending on the speaker’s intonation. With one intonation, the sentence can be interpreted literally as a sincere expression of love, but with a more sarcastic intonation, the sentence might indicate the exact opposite of what the words denote, such as a strong dislike or even outright hatred.

Different pitch and intonation can also convey whether a sentence is a statement, a command, or a question. For instance, questions frequently go up in pitch near the end of the sentence, while statements or commands do not.

Prosody in Song

Although different elements of prosody add musicality to both written and spoken language, prosody can help signal the differences between speech and song. While in speech, pitch variations convey meaning, songs utilize exact and consistent pitch values to create melodies.

In 1995, psychologist Dianna Deutsch analyzed listeners’ reaction to a phrase being repeated several times. Eventually, listeners begin to perceive the phrase as song rather than speech. This “Speech-to-Song” illusion occurs because, though the phrase is spoken not sung, repeating its exact and consistent pitch mirrors a musical structure. Listeners expect pitch variations in regular speech, so a sustained pitch signals something more musical.

Examples of Prosody in Literature

1. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”

Coleridge’s famous poem was written primarily in the ballad form. In Part 2 of the poem, the Mariner describes how his ship was stalled in the doldrums:

Water, water, every where

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where

Nor any drop to drink.

These lines are an excellent example of accentual-syllabic prosody. They alternate between iambic tetrameter (four iambs per line) and iambic trimeter (three iambs per line). The patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables, as well as the number of times they occur per line, are crucial elements of this poem’s form.

2. Chinaka Hodge, “Small Poems for Big”

Chinaka Hodge wrote an elegy for deceased rapper Biggie Smalls. Her poem is composed for twenty-four haiku—one haiku for each year of his life. In her first stanza, she writes:

when you die, i’m told

they only use given names

christopher wallace

The haiku form requires three lines consisting of a strict syllabic count: five syllables for the first line, seven syllables for the second line, and five syllables for the last line. Hodge maintains her syllabic count precisely. This excerpt from her work is illustrative of syllabic prosody—what is important is the number of syllables, rather than any patterns of emphasis.

3. Anonymous, Beowulf

The opening lines of the epic poem Beowulf are:

Hwaet! We Gar’dena in geardagum

beodcyninga, brym gefrunon

These lines are written in Old English, making their meaning difficult to understand. However, with the bold emphasis showing where the accents would be, this is a clear example of accentual prosody. The important element of these lines is the number of stresses each one contains. Here, each line contains four stresses, and the epic poem maintains this structure throughout its entire narrative.

A more modern interpretation/translation by the poet Seamus Heaney presents these lines as:

So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by

and the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness.

Heaney does not adhere to the accentual metric structure of the original as he translated the verse for meaning instead of pattern. This is a common choice made in verse translation.

4. Edmund Spencer, Iambicum Trimetrum

Spencer’s love of classical Greek and Latin poetry led him to write a poem in quantitative meter, a measure of long and short syllables that is rarely used in English poetry. This is because the English language does not have as clearly defined and agreed-upon distinctions between short and long vowels, like many other languages do. It is also because English intonation may place stress on a short syllable just as frequently as a long syllable.

Using quantitative prosody, this stanza can be understood as being comprised of patterns of long syllables, each indicated in bold type:

Now do I nightly waste wanting my kindly rest:

Now do I daily starve wanting my lively food:

Now do I always die wanting thy timely mirth.

Because of these variations in stress and duration, even if a line of English verse conforms to a particular quantitative meter, the rhythmic pattern may be impossible to discern by ear, so various readers will disagree on whether a particular vowel counts as long or short. It is because of these difficulties that English poetry is usually written in syllabic meter, accentual meter, or accentual-syllabic meter instead.

Further Resources on Prosody

The Academy of American Poets published an interesting argument in favor of the study of prosody in 21st-century poetry.

Encyclopædia Britannica has an in-depth analysis of the history of prosody in English poetry and prose.

Educator Cheree Charmello published a comprehensive overview of her teaching curriculum for introducing prosody to students in the Pittsburgh Public Schools gifted education program.