poem

What Is a Poem? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Poem Definition

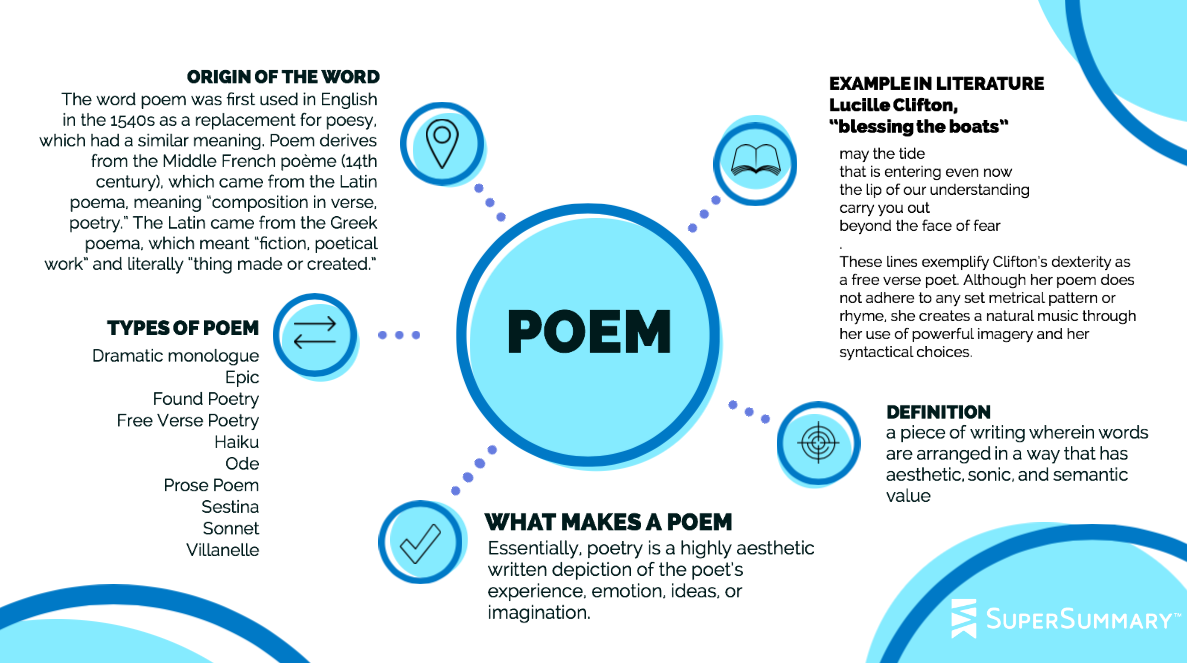

A poem (POH-im) is a piece of writing wherein words are arranged in a way that has aesthetic, sonic, and semantic value. Poems are carefully composed to convey ideas, emotions, and/or experiences vividly through literal and figurative imagery, as well as the frequent use of formal elements such as stanzaic structure, rhyme, and meter.

The word poem was first used in English in the 1540s as a replacement for poesy, which had a similar meaning. Poem derives from the Middle French poème (14th century), which came from the Latin poema, meaning “composition in verse, poetry.” The Latin came from the Greek poema, which meant “fiction, poetical work” and literally “thing made or created.”

What Makes a Poem

It’s not easy to determine set criteria for what makes a poem. Traditionally, people used to categorize poetry as literature written only in rhymed verse, but that isn’t correct. Although historically poetry adhered to set formulas of rhyme and meter, free verse—the most common form of contemporary poetry—does not. Free verse is unmetered and either does not rhyme at all or tends to use slant rhymes. In addition to free verse, many other types of poetry don’t rhyme or follow metrical patterns.

Additionally, the definition of poetry as literary work that is written in verse—as opposed to prose, the style novels are typically written in—is also no longer true. There are novels written in verse, just as there’s an entire genre of poetry written in prose (prose poetry). There’s also a type of poetry that consists of only one sentence written out as a single line (the monostitch).

Unlike many other literary forms, there’s no universally accepted collection of elements that any given poem must contain. Poetry lends itself to highly romantic, dramatic definitions. Consider Jim Harrison’s definition, “the language your soul would speak if you could teach your soul to speak,” or Percy Bysshe Shelley’s, “the expression of the imagination.”

Essentially, poetry is a highly aesthetic written depiction of the poet’s experience, emotion, ideas, or imagination. Although any given poem need not contain all of these elements, poetry does consistently employ literary devices such as rhyme, meter, imagery, metaphor, simile, onomatopoeia, alliteration, and refrain to engage the reader.

Types of Poem

There are many different types of poems, but the following are some of the most common.

- A dramatic monologue is a type of poem where a character speaks without interruption and reveals surprising information about themselves or their situation. This type of work is also called a persona poem.

- Epics are long poetic works that tell a story, typically from the third-person point of view. They tend to follow a idyllic hero who represents their culture, and the plot is usually of cultural, historical, and/or religious importance.

- Found poetry is composed entirely from snippets of text taken from outside sources; for example, movie titles or lines from a newspaper horoscope column. In addition to typical found poems, there are also centos, which are made up of 100 lines from 100 other poems, and erasures, where a poet takes a page of text and crosses out most words, creating a poem from the ones that remain.

- Free verse poetry, as stated, does not follow any set metrical pattern or rhyme scheme. Instead, the poet is free to compose the poem however they wish without following any rules.

- Haiku is a type of Japanese poetry consisting of a tercet (three-line stanza) where the first line has a syllabic count of five, the second line consists of seven syllables, and the final third line returns to the five count. These three lines do not rhyme.

- Odes are lyric poems, often elevated or formal in manner, and written in praise of someone or something. There are three types of odes: Pindaric, Horatian, and irregular.

- Prose poems are, of course, poems written in prose. Rather than using line breaks and stanzaic structure, these poems follow the formatting conventions of prose and are written in a paragraph or series of paragraphs.

- Sestinas are poems comprised of seven stanzas that follow a strict, complex structure. The first six stanzas are sestets (six-line stanzas), and the final stanza is a tercet. The last word of each line of the first six stanzas must repeat in a certain pattern, and those six end-words all recur in the final stanza (the envoi) according to a specific order.

- Sonnets are 14-line poems that follow set patterns of rhyme and meter and whose mood or tone must change after the eighth line (the volta). There are two primary types of sonnets: the English (or Shakespearean) sonnet and the Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet.

- Villanelles are French poems composed of 19 lines. These poems contain five tercets (three-line stanzas) and a final quatrain (four-line stanza). They utilize two repeating rhymes and two refrains.

Notable Poets

- John Ashbery, “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”

- Charles Baudelaire, “The Cat”

- Basho, “In Kyoto”

- William Blake, “The Tyger"

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “How Do I Love Thee?"

- Robert Browning, “My Last Duchess”

- Gwendolyn Brooks, “We Real Cool”

- Robert Burns, “To a Haggis”

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”

- Emily Dickinson, “My Life had stood-a Loaded Gun”

- John Donne, “Death, be not proud”

- T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

- Robert Frost, “Desert Places”

- Homer, The Odyssey

- Langston Hughes, “Theme for English B”

- Allen Ginsberg, “Howl”

- John Keats, “Ode to a Nightingale”

- Edna St. Vincent Millay, “Recuerdo”

- Ovid, The Metamorphoses

- Pablo Neruda, “The Song of Despair”

- Rumi, “Where did the handsome beloved go?”

- Sappho, “Fragment”

- William Shakespeare, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?"

- Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Ozymandias”

- Sylvia Plath, “Lady Lazarus”

- Alfred Lord Tennyson, “The Charge of the Light Brigade”

- Walt Whitman, “When Lilacs Kast in the Dooryard Bloom’d”

- William Wordsworth, “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”

- William Butler Yeats, “The Second Coming”

Examples of Poems

1. Lucille Clifton, “blessing the boats”

Clifton opens her famous poem with the lines:

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

These lines exemplify her dexterity as a free verse poet. Although her poem doesn’t adhere to any set metrical pattern or rhyme, she creates a natural music through her use of powerful imagery and her syntactical choices.

2. Elizabeth Bishop, “The Art of Losing”

Bishop’s poem was originally written in free verse; however, during revisions, she decided it would be more powerful with the rhyme and refrain elements of the villanelle form. Her opening stanza sets up the composition that all subsequent stanzas amplify:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

The first refrain is the first line of the first stanza, which appears as the last line in the second stanza. You can also see the beginning of Bishop’s ABA rhyme scheme.

3. Ron Padgett, “Haiku”

Ron Padgett’s poem is a clever embodiment of the eponymous form. The poem reads, in its entirety:

First: five syllables.

Second: seven syllables.

Third: five syllables.

Padgett’s title states the form his poem will take. His short work both tells the readers what structure a haiku requires while simultaneously perfectly fulfilling those requirements.

4. Mattea Harvey, “Implications for Modern Life”

Harvey’s prose poem eschews line breaks and stanza breaks in favor of standard paragraph formatting. In her first few lines, Harvey presents a strong visual situation described in prose:

The ham flowers have veins and are rimmed in rind, each petal a little meat sunset. I deny all connection with the ham flowers, the barge floating by loaded with lard, the white flagstones like platelets in the blood-red road. I’ll put the calves in coats so the ravens can’t gore them, bandage up the cut gate and when the wind rustles its muscles, I’ll gather the seeds and burn them.

Throughout the poem, she utilizes other standard elements of poetry—alliteration, imagery, metaphor, and personification—which give her work the same sonic elegance and vivid visual power that readers are accustomed to seeing in poetry.

5. Nate Marshall, “pallbearers”

In the first stanza, Marshall sets up the sestina structure he must follow:

Dom, Kenny, Shaun, Bark & i were close as a coffin.

promised we would always be tight.

we made it to every middle school dance.

weaving through crowds of kids we kept moving

behind a nervous girl’s hips, mesmerized by the split

of skirts & smiles at our request. we didn’t know much.

The last word of each line—coffin, tight, dance, moving, split, and much—reappear at the end of different lines in subsequent stanzas of the poem, following the traditional sestina structure. Unlike many sestinas, however, Marshall uses a more experimental approach to capitalization, using lowercase letters at the beginning of each sentence and capitalizing only the names of the speaker’s friends as another way to emphasize their importance.

6. William Shakespeare, “Sonnet XXIX”

Shakespeare’s sonnet opens with his speaker declaring:

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries

And look upon myself and curse my fate

These opening four lines are written in iambic pentameter, which means that there is a pattern of five metrical feet per line and each foot consists of a short, unstressed syllable followed by a long, stressed syllable. This metrical pattern is a required part of the English sonnet, as is the rhyme scheme of ABAB that these lines follow. Later in the sonnet, at the eighth line, the poem takes a turn and shifts into a new direction, giving it a sense of resolution.

Further Resources on Poems

The poet Mark Yakich wrote a lovely analysis of poetry for The Atlantic online’s “Object Lessons” series.

Matthew Zapruder has an excellent book explaining the importance of poetry, as well as easy ways to understand it.

The Academy of American Poets’ website is an excellent source for additional poetry information, as is the website for The Poetry Foundation.

The Best American Poetry anthology series runs a blog full of original posts by poets, as well as interviews, essays about the world of poetry, new poems, and other poetry commentary.