free verse

What Is Free Verse? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Free Verse Definition

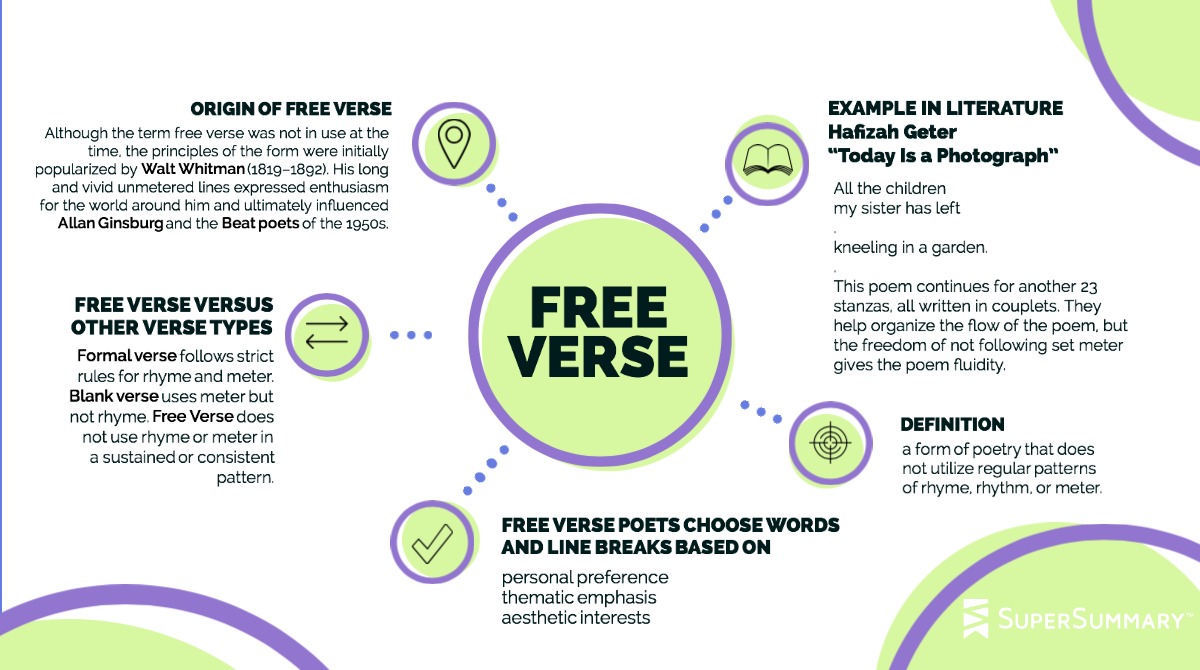

Free verse (furEE VURHss) is a form of poetry that does not utilize regular patterns of rhyme, rhythm, or meter. Although rhyme and rhythm may occur, there is no standard regulating them to which the poet must adhere. Free verse poems tend to mimic the patterns of natural speech, as well as build upon and play with flights of imagery and repeated sounds.

The term free verse is a literal translation of the identical French form vers libre (1880s), whose adherents no longer wanted to be constrained by the restrictions of the alexandrine form. The term was adapted into English and American poetry in the early 1900s by modernist poets.

Free Verse and Other Verse Types

When it comes to literary tools such as rhyme and meter, poetry can be divided into three types of verse: formal, blank, and free.

Formal Verse

Poems written in formal verse are constructed according to strict rules for rhyme and meter. Consider Shakespeare’s sonnets. In “Sonnet 29,” he writes:

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself and curse my fate

These lines are written in formal verse. They follow a strict metrical pattern (iambic pentameter) and a rhyme scheme of ABAB.

This type of verse uses meter but not rhyme. Generally, blank verse was written in iambic pentameter. Plays by Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, as well as John Milton’s famous epic poem Paradise Lost, were written in blank verse.

More modern poets, like W. B. Yeats and Robert Frost, often wrote in blank verse as well. For example, in “Mending Wall,” Frost writes:

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

These lines are all written in iambic pentameter, but they do not rhyme, making them blank verse.

Free Verse

As discussed, poetry that doesn’t use rhyme or meter is considered free verse. While rhyme or metrical patterns may occasionally occur in a free verse poem, the poem is does not sustain them as consistent patterns.

Most modern poetry is written in free verse. For example, National Book Award finalist Carmen Giménez Smith’s poem “Happy Trigger” uses short lines, surprising line breaks, and strong imagery to engage readers instead of relying on meter or uniform line breaks. In her first stanza, she writes:

Off-season and in

the burnt forest

of my nightgown, a feral

undergrowth that marks

me as burial site—

to be still enough or

just enough.

The off-kilter line breaks, jagged lines, repetition of the word enough, and surprising and bleak imagery keep the reader’s interest. Her poem is unsettling in topic and tone, and her choice to write in free verse, rather than employing the more soothing patterns of rhyme and meter, adds to the poem’s disturbing power.

Why Poets Write in Free Verse

Poets write in free verse because it allows for more freedom. Rhyme and meter are powerful tools, but they also dictate the form a poem takes. Many poets prefer to allow their imagination to unfold without needing to shape their words to pre-set rules.

Free verse allows the poem to choose words and line breaks based on personal preference, thematic emphasis, or aesthetic interests rather than needing their diction and syntax to adhere to specific sound choices or syllabic stress patterns.

How Free Verse Became Popular

Free verse has been popular for a long time. Although the form seems modern, it has a long, rich tradition.

Although the term free verse was not in use at the time, the principles of the form were initially popularized by Walt Whitman (1819–1892). His long and vivid unmetered lines expressed enthusiasm for the world around him and ultimately influenced Allan Ginsburg and the Beat poets of the 1950s.

The English and American poets who were influenced by free verse in the 1900s included modernist and imagist poets such as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, Carl Sandburg, and Wallace Stevens. Many of the poets of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes, also wrote in free verse, as did confessional poets from the ‘50s and ‘60s, such as Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Adrienne Rich, and New York School poets from the same era, such as Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and James Schuyler.

Since the 1970s, if not sooner, the default form of American poetry has been free verse, and it is now rare to see contemporary poets who consistently writing in formal or closed-form verse.

Notable Free Verse Poets

- Matthew Arnold, “Dover Beach”

- John Ashbery, “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”

- Gwendolyn Brooks, “when you have forgotten Sunday: the love story”

- Lucille Clifton, “mulberry fields”

- Hart Crane, “Voyages”

- e. cummings, “i carry your heart with me”

- S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

- Allen Ginsburg, “A Supermarket in California”

- Joy Harjo, “A Map to the Next World”

- Langston Hughes, “I, Too”

- June Jordan, “Poem about My Rights”

- Li-Young Lee, “This Room and Everything in It”

- Ada Limón, “How to Triumph Like a Girl,”

- Audre Lorde, “Coal”

- Marianne Moore, “Poetry”

- Frank O’Hara, “Having a Coke with You”

- Mary Oliver, “Journey”

- Sylvia Plath, “Tulips”

- Ezra Pound, “The Return”

- Adrienne Rich, “Planetarium”

- Carl Sandburg, “Chicago”

- Vijay Seshadri, “The Disappearances”

- Anne Sexton, “Winter Colony”

- Wallace Stevens, “Sunday Morning”

- Walt Whitman, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”

- William Carlos Williams, “The Red Wheelbarrow”

Examples of Free Verse in Literature

1. Walt Whitman, “Sometimes with One I Love”

Whitman’s short love poem, “Sometimes with One I Love,” reads in its entirety:

Sometimes with one I love I fill myself with rage for fear I effuse unreturn’d love,

But now I think there is no unretrun’d love, the pay is certain one way or another

(I loved a certain person ardently and my love was not return’d,

Yet out of that I have written these songs).

Whitman’s flowing lines do not follow any formal metrical pattern, nor do they rhyme. Instead, they freely follow the twists and turns of Whitman’s thoughts, creating an expressive and honest power.

2. Louise Erdrich, “Windigo”

In the opening stanza to her poem, Erdrich speaks through the voice of a windigo—a ravenous winter spirit:

You knew I was coming for you, little one,

when the kettle jumped into the fire.

Towels flapped on the hooks,

And the dog crept off, groaning,

To the deepest part of the woods.

This free verse poem is also a dramatic monologue, as the persona speaking is the windigo rather than Erdrich herself. The narrative that unfolds is a version of an indigenous Chippewa story about a windigo, which Erdrich elects to relay through the monster’s own voice.

3. Hafizah Geter, “Today Is a Photograph”

Geter begins her poem with the following lines:

All the children

my sister has left

kneeling in a garden.

It is an orange spider

crushed beneath their teeth,

becoming heirs

to each other’s hungers.

This poem continues for another 23 stanzas, all written in couplets. They help organize the flow of the poem, but the freedom of not following set meter gives the poem fluidity.

4. Chen Chen, “When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities”

Chen Chen’s poem is written in free verse couplets that utilize the power of repetition to create a pattern.

To be a good

ex/current friend for R. To be one last

inspired way to get back at R. To be relationship

advice for L. To be advice

for my mother. To be a more comfortable

hospital bed for my mother. To be

no more hospital beds. To be, in my spare time,

America for my uncle, who wants to be China

for me….

Although Chen Chen’s poem does not adhere to any rigid metrical pattern or rhyme scheme, he creates a cumulative power through his repetitions of to be.

Further Resources on Free Verse

The Academy of American Poets published an excellent overview of the history of free verse by poet Edward Hirsch.

Book Riot has a wonderful list of 50 free verse poems.

The late poet Mary Oliver has a great chapter on free verse (“Verse That Is Free”) in her book A Poetry Handbook.

Poet Marjorie Perloff’s excellent essay “After Free Verse: The New Non-Linear Poetries” explores free verse.