frame story

What Is a Frame Story? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Frame Story Definition

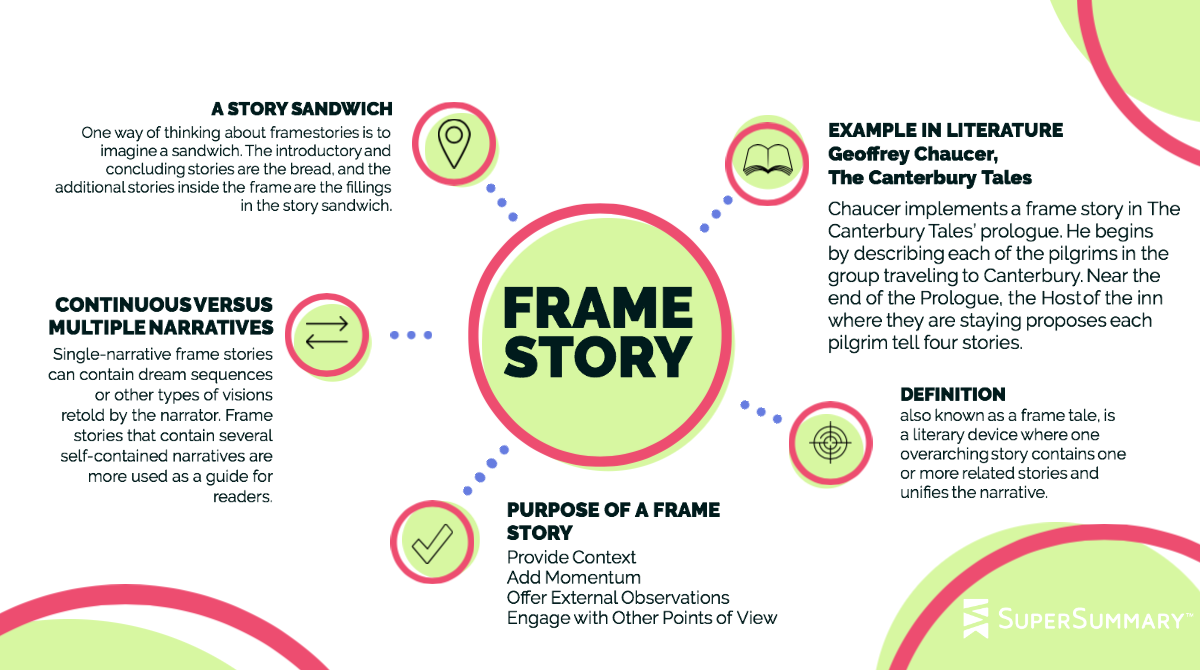

A frame story (FRAYmuh STORE-ee), also known as a frame tale, is a literary device where one overarching story contains one or more related stories and unifies the narrative.

It is a very common literary device that has been used in classical literature, including such works as Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron. It remains a popular narrative tool and can be seen outside literature in modern movies and television shows, such as Inception, Titanic, and How I Met Your Mother.

How Frame Stories Are Formed

Frame stories occur when a main or supporting character begins telling a story to other characters or the reader, like in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. They can also have a narrator who is actively writing the story being told, like in William Goldman’s The Princess Bride. The “frame” is the introductory and concluding narrative that surround the other stories.

One way of thinking about frame stories is to imagine a sandwich. The introductory and concluding stories are the bread, and the additional stories inside the frame are the fillings in the story sandwich.

The Purpose of a Frame Story

There are many reasons why authors use frame stories, depending on what their literary work needs to achieve.

Provide Context

A frame story can add greater context to the stories within it. The frame narrative surrounding Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner introduces the old sailor and clarifes the story he subsequently tells.

Add Momentum

A frame story can guide readers from one story to the next, supplying additional information and graceful transitions. In the collection of Middle Eastern folktales One Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade and her perilous marriage are introduced as a framing device. Each night, Scheherazade starts telling her husband a story but doesn’t finish it. This motivates him to keep her alive, rather than kill her like his other brides. Scheherazade incorporates multiple narratives—and additional frames—within her stories, and the framing device of her weaving these tales allows the book to move seamlessly from one story to the next.

Offer External Observations

A frame story can present additional insights into the narrative(s) it encloses. It can also add moments of levity or elicit emotional responses that guide the audience. In the movie version of The Princess Bride, the frame story is a grandfather telling his grandson a story of love and adventure to distract the boy, who’s sick in bed. The grandson is (initially) less interested in “the love parts,” but his grandfather provides witty commentary that more closely mirrors the audience’s interests.

Engage with Other Points of View

A frame story can employ a change in point of view or narrator, as well as add multiple levels of interpretation. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the frame story allows for multiple narrators—Captain Robert Walton, Victor Frankenstein, and The Creature. This gives readers a variety of perspectives about the events of the book and, ultimately, ensures they finish the book feeling sympathy for the seemingly villainous monster.

Continuous vs. Multiple Narratives within Frame Stories

A frame story can contain one single (or continuous) story or multiple stories, each with its own narrative uses.

When the frame holds a single story, it is often used to guide readers’ attitude about the work and the narrator. Typically, the frame acts as a procatalepsis—a counterargument wherein a speaker objects to their own argument and then immediately discounts it to strengthen their position. A frame supporting a continuous narrative allows the author to raise and immediately respond to questions or objections about the contained story before readers have a chance to protest. This helps legitimize the main narrative.

Single-narrative frame stories can contain dream sequences or other types of visions retold by the narrator. Other times, attaching a frame story to a single narrative can be used as an aspect of characterization. In the movie Amadeus, the frame story shows young Mozart’s genius as well as the unreliability and jealousy of his rival Salieri, who recounts the embedded narratives.

Frame stories that contain several self-contained narratives are more used as a guide for readers. They ensure smooth transitions between the narratives and provide useful contextual reminders. In these cases, the frame story ties together different stories that might otherwise feel disparate and unconnected.

Frame Stories and Nested Narratives

In addition to surrounding multiple narratives, there are frame stories that contain nested narratives. This is when an introductory story—the frame—leads into another story, which itself contains one or more stories.

Imagine a Russian doll. The doll can be taken apart to reveal there’s a smaller doll inside, then another doll inside that one, and so on. Nested narratives work in the same way. There’s a larger story that contains a secondary story, which in turn introduces and surrounds a tertiary story, and so on. The larger frame story contains all the stories nested within it.

These nested narratives allow multiple layers. In the movie Inception, protagonist Cobb enters the dreams of a businessman named Robert to implant an idea into Robert’s subconscious. In that first dream, Cobb puts Robert to sleep again and follows him into a second layer of dreaming, which soon leads to a third dream and then a final fourth layer. Eventually, the final dream ends, allowing Cobb to rise back through each layer of dreaming and return to consciousness. All the dreams are nested inside each other as well as within the larger narrative taking place outside of the dreams.

Frame Stories and Flashbacks

Flashbacks are a device used within a frame story to give important backstory information. This is a useful technique in visual storytelling. In the movie Citizen Kane, interviews conducted by a newspaper reporter frame individual stories about the dead tycoon’s life. In Fight Club, based on the Chuck Palahniuk novel of the same name, most of the movie is one long flashback. In these films, the framing story takes place in the present, and the flashbacks tell stories about past events.

Although flashbacks cannot exist outside a frame story, since the latter gives context for the former, there are many frame stories that don’t contain flashbacks. Frame stories don’t need their contained narratives to directly connect back to them. Instead, frame stories allow the narrator to tell stories unrelated to them.

Frame Stories in Pop Culture

Frame stories are frequently used in movies and television shows to intrigue audiences by hinting at things to come in the main narrative.

- The movie Titanic begins with an elderly woman named Rose telling the story of her voyage on that ill-fated ship. Most of the movie shows the adventures of young Rose and her beloved Jack, but the film returns to the elderly Rose at the end.

- The movie The Notebook, based on the Nicholas Sparks book of the same name, shares a similar use of a frame story. It begins with an elderly man in a nursing home telling stories to an elderly woman who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. The man tells her a series of love stories about a young couple falling in love. As these stories progress, acting as the main narrative, the audience realizes that the elderly couple is the same couple from the man’s stories. The movie ends in the present, when the couple dies on the same night.

- The television show How I Met Your Mother uses a frame in each episode. The sitcom begins with the main character, Ted, in 2030 recounting to his children all the events that led to meet their mother decades earlier. The main action takes place in the past, exploring a younger Ted’s adventures, but the episodes begin and end by showing Ted’s children in the future, listening and occasionally commenting on his stories.

Examples of Frame Stories in Literature

1. Anonymous, One Thousand and One Nights

In this collection of Middle Eastern folklore, the frame story is the tale of Scheherazade (stylized Shahrazád, who agreed to marry the King, despite knowing that he kills his brides at dawn the morning after their wedding. Her plan to save her life (and the lives of countless other women) is to begin telling the King a story on their wedding night. The first of these stories, “The Story of the Merchant and the Jinnee,” begins with her saying:

It has been related to me, O happy King, said Shahrazád, that there was a certain merchant who had great wealth, and traded extensively with surrounding countries; and one day he mounted his horse, and journeyed to a neighbouring country…

This story is so compelling that, when dawn comes and she hasn’t reached the conclusion, the King spares her life so she can finish telling it the next night. Of course, Scheherazade’s stories never end, as she nests one narrative into the next and cleverly begins new stories as soon as the old ones end. She eventually survives for so many days that the King falls in love with her and spares her life.

By having Scheherazade tell these stories, the frame creates a continuous thread for an otherwise unconnected series of folktales.

2. Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales

Chaucer implements a frame story in The Canterbury Tales’ prologue. He begins by describing each of the pilgrims in the group traveling to Canterbury. Near the end of the Prologue, the Host of the inn where they are staying proposes that each pilgrim entertains the group:

“Lordynges,” quod he, “now herkneth for the beste;

But taak it nought, I prey yow, in desdeyn;

This is the poynt, to speken short and pleyn,

That ech of yow, to shorte with oure weye

In this viage, shal telle tales tweye,

To Caunterbury-ward, I mene it so,

And homward he shal tellen othere two,

Of aventúres that whilom han bifalle.

And which of yow that bereth hym beste of alle,

That is to seyn, that telleth in this caas

Tales of best sentence and moost solaas,

Shal have a soper at oure aller cost […]”

The Host says each pilgrim must tell four stories—two on the way to Canterbury and two on the way back—and that whomever is the best storyteller will receive a free meal, at the expense of the other pilgrims. This framing device allows Chaucer to have each character introduce themselves, and it opens up the poem so each character can tell multiple embedded stories.

3. Randall Horton, Hook

In Randall Horton’s autobiography, the poet and musician tells his life story. Horton was a young man of great promise attending Howard University when he became involved with drugs. He eventually became an addict, homeless, and a felon. Within Horton’s personal story, he introduces the character Lxxxx, a young Latina awaiting trial on drug charges. Horton asks Lxxxx to share her own story through a series of letters. In her first letter, Lxxxx writes:

Dear Randall,

There are certain situations about the past and family that are hard to discuss.

For years I’ve been trying to forget, but as you say, one cannot shake the past;

it will affect you—haunt you.

Lxxxx details her past and how her experiences led her to her current situation. Horton uses the frame of his own life to introduce Lxxxx, and both their stories show the way racism, as well as difficult family situations, can affect the course of people’s lives.

Further Resources on Frame Stories

Gregory O’Dea wrote an interesting article about the use of frame stories within Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Dorrance Publishing Company has a great guide on how to write a frame story.

Ariel Katz wrote a short examination on the Ploughshares site about using frame stories to illustrate the passage of time.