conceit

What Is a Conceit? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Conceit Definition

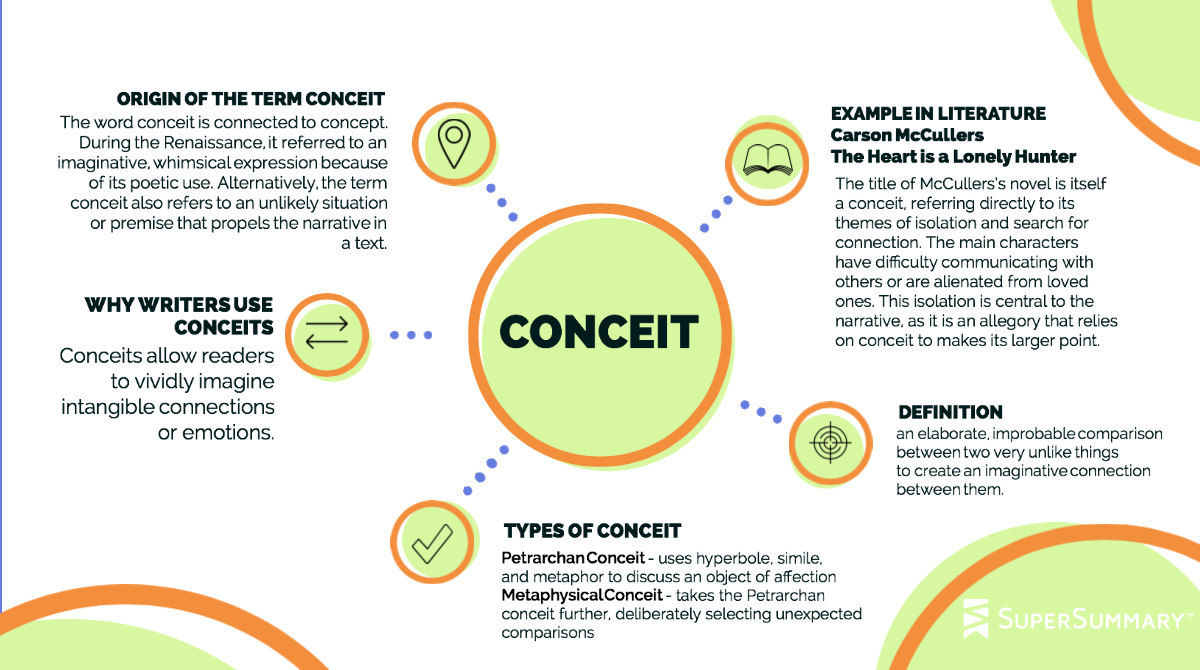

A conceit (kuhn-SEAT) is an elaborate, improbable comparison between two very unlike things to create an imaginative connection between them. As a result, conceits are often mentioned in connection with simile, extended metaphors, and allegories since they also use comparisons or symbolic imagery. It’s a device commonly used in poetry.

The word conceit is connected to concept. During the Renaissance, it referred to an imaginative, whimsical expression because of its poetic use. Alternatively, the term conceit also refers to an unlikely situation or premise that propels the narrative in a text.

Types of Conceits

There are two main types of conceit: Petrarchan and metaphysical.

Petrarchan Conceit

The Petrarchan conceit, popularized by Italian classic poet Francesco Petrarch, uses hyperbole, simile, and metaphor to discuss an object of affection, often using extended metaphors to center the poem around this conceit. Edmund Spenser’s Epithalamion provides several examples of conceit. An ode to his wife, Spenser uses various figures of speech to convey his wife’s beauty and innocence. He says her eyes are “like sapphires shining bright” and compares her to a turtle dove, which symbolizes devoted love. By highlighting similarities between his bride and various animals and Greek myths, he builds an elaborate connection between her and the concept of everlasting love.

Metaphysical Conceit

The metaphysical conceit takes the Petrarchan conceit further, deliberately selecting unexpected comparisons. These urge the reader to determine the expression’s meaning and understand the intellectual argument the poet is making. This type of conceit also uses hyperbole, simile, and metaphor.

John Donne’s “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” uses conceit when he compares two lovers’ souls to “twin compasses” moving in unison. Using analogy, Donne paints a picture of the lovers being like compass magnets, which are pulled in certain directions and, in this case, opposite ones.

The History of Conceits

Conceit in Classical Poetry

During the Italian Renaissance, Petrarch heavily featured conceits in his poetry, focused on illustrating vivid comparisons between the poet’s lover and nature. As the device gained prominence, English Renaissance poets began using it as well.

Consider this excerpt from William Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 97”:

How like a winter hath my absence been

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year!

What freezings have I felt, what dark days seen!

What old December’s bareness everywhere!

In the sonnet, Shakespeare uses the seasons—winter, in this excerpt—to describe the loneliness of being separated from a lover. Such comparisons quickly gained popularity to the point of overuse, and by the end of the 16th century, the literary device was considered obvious and trite.

The Development of the Metaphysical Conceit

During the 17th century, poets reworked the Petrarchan technique, developing the metaphysical conceit, exemplified in John Donne’s “The Flea”:

Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deniest me is;

It suck’d me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be.

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead;

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pamper’d swells with one blood made of two;

And this, alas! is more than we would do.

The poem’s speaker attempts to change his lover’s mind after she refuses to sleep with him. He makes an odd comparison between their both being bitten by the same flea and marriage. This is an attempt to convince her that physical intimacy would be innocent and natural because they are already joined, in a way, within the flea.

Metaphysical conceits became popular as their unexpected nature captured poets’ and readers’ imagination. However, as with the Petrarchan conceit, its overuse led to a rejection of the device. After a long period of disuse, the conceit returned in its modern and abbreviated form during the 19th century, such as in works by T.S. Eliot and Emily Dickinson, and is still present in modern poetry in this less excessive capacity.

Conceit in Modern Literary Criticism

In addition to literature, the term conceit is also used in modern literary criticism. In this context, the word refers to an extended metaphor that describes a concept or situation that doesn’t or is unlikely to exist but is required to further the text’s premise. When used positively, the term refers to the complexity and effectiveness of this extended rhetorical device to continue the narrative. When used negatively, it refers to the contrived or exaggerated use of this rhetorical device.

Why Writers Use Conceits

Conceits allow readers to vividly imagine intangible connections or emotions. The Petrarchan conceit focuses on evoking and depicting emotion through its description of a subject, encouraging the reader to imagine, feel, or see what the writer does. The metaphysical conceit follows this effect to challenge readers on an intellectual level and allowing the writer to demonstrate their intellectual and imaginative skill.

However, when conceits are overdone, they fail to engage the reader. Rather than relate to the reader, an overdone conceit can be cliché or stale. In these cases, the device falls flat, either because it doesn’t evoke the emotion it’s meant to or because the comparison is too much of a stretch for the reader to accept.

Conceits and Other Literary Devices

Conceits and Idioms

Outside of literature, conceits are commonly found in idioms.

- “Dead as a doornail”: This common phrase refers to something irrevocably dead or obsolete. Unexpected as the reference sounds, the logic is that a doornail is clenched when driven into the door, rendering it unavailable for reuse. Someone who has died or something that has been surpassed in some capacity can be considered as similarly unavailable.

- “The apple of discord”: This idiom draws on Greek mythology, referring to the golden apple that sparked the Trojan War. The phrase refers to something that is causing tension.

- “Steal someone’s thunder”: The statement, while seemingly nonsensical, refers to someone stealing another’s idea. The phrase originates from an incident in the 18th century when playwright John Dennis’s thunder sound effect machine was copied without his consent.

- “Fit as a fiddle”: Another common idiom with an unexpected comparison, this phrase refers to someone being in good health. Its origin isn’t definitively known, but it may draw from instruments’ upkeep as musicians must care for them extensively keep them in working order.

Conceits and Metaphors

Conceits are often mentioned alongside extended metaphors. This connection is not unwarranted; modern writers use the terms conceit and extended metaphor interchangeably because both refer to metaphors that take place over the course of a text. However, when referring to more traditional, poetic roots, conceits are defined as an elaborate type of extended metaphor because it makes the case for a surprisingly dissimilar comparison.

Conceits and Allegories

Allegories may use conceits, extended metaphors, or similes to express abstract ideas or principles through characters and narrative. These literary devices are not necessarily allegories on their own; they are merely tools to build a message, rather than express a concept in an imaginative way.

Examples of Conceit in Literature

1. William Shakespeare, “Sonnet 130”

Shakespeare’s famous sonnet pokes fun at the Petrarchan conceit:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

Throughout the sonnet, Shakespeare uses conceit to compare his lover to nature. However, he comically contradicts the conceit’s usual favorable descriptions. Instead of lovingly comparing her to the wonders of nature, he says nature’s beauty far exceeds her own. In the end, he reveals that it is the woman’s imperfections that make him love her.

2. Adrienne Rich, “Diving into the Wreck”

Rich’s poem provides a more contemporary form of conceit:

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

Using the conceit of exploring a shipwreck, the speaker reflects on herself and her past understanding of the world. This use of the literary device is more nuanced than the conceits found in classical poetry. Rather than continuing to make direct comparisons throughout the poem, Rich allows the poem to flow and only explicitly returns to the shipwreck image when needed.

3. Carson McCullers, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

The title of McCullers’s novel is itself a conceit, referring directly to its themes of isolation and search for connection. The main characters have difficulty communicating with others or are alienated from loved ones. This isolation is central to the narrative, as it is an allegory that relies on conceit to makes its larger point.

Further Resources on Conceit

Najat Ismaeel Sayakhan’s The Teaching Problems of English Poetry in the English Departments delves further on different variations of Petrarchan and metaphysical conceits in poetry.

Kaplan has a list of Shakespearean idioms, which often use conceits.