anapest

What Is Anapest? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Anapest Definition

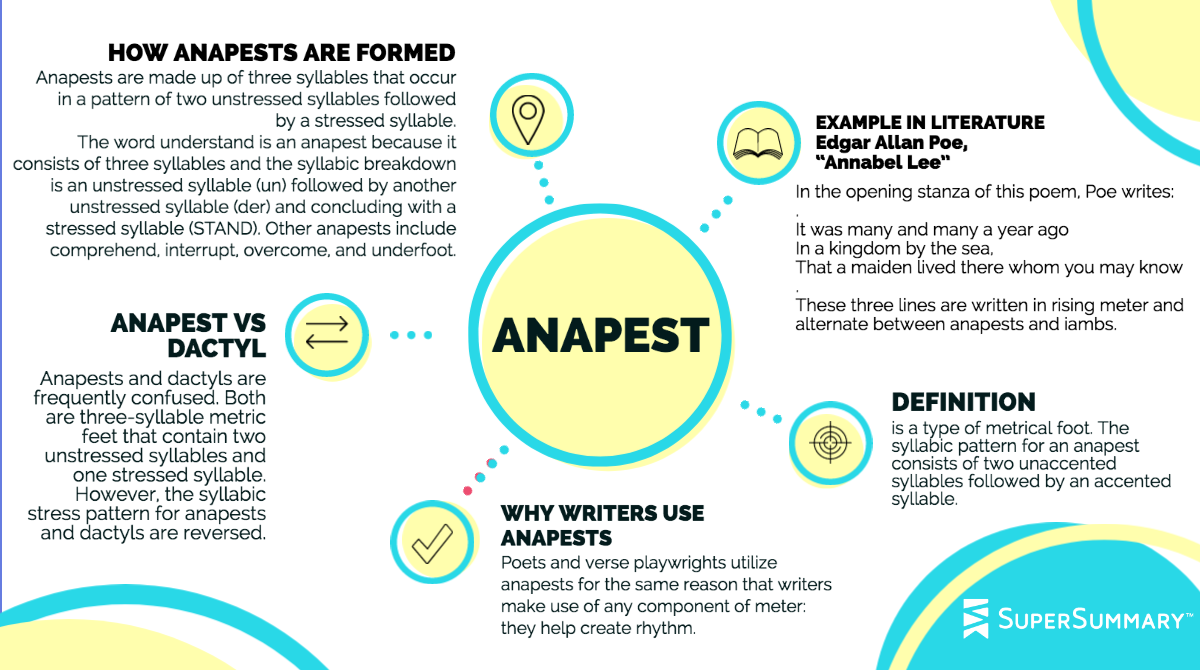

An anapest (ann-uh-pehst) is a type of metrical foot. The syllabic pattern for an anapest consists of two unaccented syllables followed by an accented syllable. Anapests can be seen throughout English poetry and verse plays, but they are most frequently employed in comic verse, such as limericks.

The word anapest was first used in English in the 1670s. It derives from the Latin anapaestus, which comes from the Greek anapaistos, meaning “struck back, rebounding.” The Greek term is a combination of ana, meaning “back,” and paiein, “to strike.” The idea of rebounding back relates to how the syllabic pattern of the anapest is the reverse of the dactyl, another type of metrical foot.

How Anapests Are Formed

Anapests are made up of three syllables that occur in a pattern of two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable.

The word understand is an anapest because it consists of three syllables and the syllabic breakdown is an unstressed syllable (un) followed by another unstressed syllable (der) and concluding with a stressed syllable (STAND). Other anapests include comprehend, interrupt, overcome, and underfoot.

Anapest vs. Dactyl

Anapests and dactyls are frequently confused. Both are three-syllable metric feet that contain two unstressed syllables and one stressed syllable. However, the syllabic stress pattern for anapests and dactyls are reversed.

In anapests, the final syllable is stressed, and it is preceded by two unstressed syllables. Dactyls stress the first syllable, leaving the second and third syllable unstressed. For example: poetry (PO-eh-tree) or, ironically, the word anapest.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Meter

Anapests are metrical feet, which means they play a crucial role in determining meter. There are two overarching categories of verse meter.

Qualitative (or Accentual) Meter

This type of meter refers to patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables that occur at regular intervals in the poetic line. These syllabic patterns are known as feet and include anapests, dactyls, iambs, spondees, and trochees. The type of foot and number of times it occurs per line determines qualitative meter. Most English poetry is based on qualitative meter.

In qualitative meter, an anapest follows the syllabic stress pattern of an unstressed syllable followed by another unstressed syllable and concluding with a stressed syllable.

Quantitative Meter

This type of meter is dictated by syllabic weight rather than syllabic stress. Syllabic weight refers to the length of the syllable in terms of pronunciation. For example, a short syllable takes less time to pronounce than a long syllable. Quantitative meter is rare in English poetry, but it was a crucial component of classical Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Sanskrit poetry.

In quantitative meter, the stress patterns of syllables are irrelevant. Instead, syllabic weight determines the meter. An anapest in quantitative meter consists of two short syllables followed by a long syllable.

Why Writers Use Anapests

Poets and verse playwrights utilize anapests for the same reason that writers make use of any component of meter: they help create rhythm. The syllabic pattern of repeated anapests or anapests varied with other metrical feet brings melody and harmony to literary works. This musical quality helps keep readers engaged. Anapests can also serve as mnemonic devices as repeated patterns of sound are useful in memorization. As anapests end with a strong syllable, anapestic meter also is useful for creating strong rhymes.

Examples of Anapest in Literature

1. Lord Byron, “The Destruction of Sennacherib”

Perhaps the most famous example of the use of anapest in English literature is Lord Byron’s poem “The Destruction of Sennacherib.” Byron begins this poem with a description of the attacking troops:

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea,

When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee.

This stanza, like all the stanzas that follow, is written using anapests. The poem uses four anapests per line, which means it is written in anapestic tetrameter.

2. Edgar Allan Poe, “Annabel Lee”

In the opening stanza of this poem, Poe writes:

It was many and many a year ago

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden lived there whom you may know

These three lines are written in rising meter and alternate between anapests and iambs. The first line consists of three anapests and an iamb, the second line opens with an anapest followed by two iambs, and the third line is equally comprised of anapests and iambs. This shifting pattern of syllabic stress create a lovely haunting melody.

3. Clement Clarke Moore, “A Visit from St. Nicholas”

Moore’s famous Christmas poem also uses anapests.

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds;

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads

This poem is written in consistent anapestic meter. The meter is primarily anapestic tetrameter and anapestic trimeter. The anapestic meter gives the poem a pleasing harmony. The strong AABB end rhymes, which are often aided by the stressed third syllable of the anapests, also contribute to the poem’s harmony and render it easy to memorize.

Further Resources on Anapests

The Society of Classical Poets has a very useful guide to meter, including the role played by anapests.

The Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica wrote a brief guide to the history of anapest.

According to research published by Frontiers in Psychology: Language Sciences, the use of meter (including anapestic meter) in poetry can create specific emotional and aesthetic effects in readers.

Limericks are a type of comic verse which often use anapests. This guide goes into depth scanning limericks.